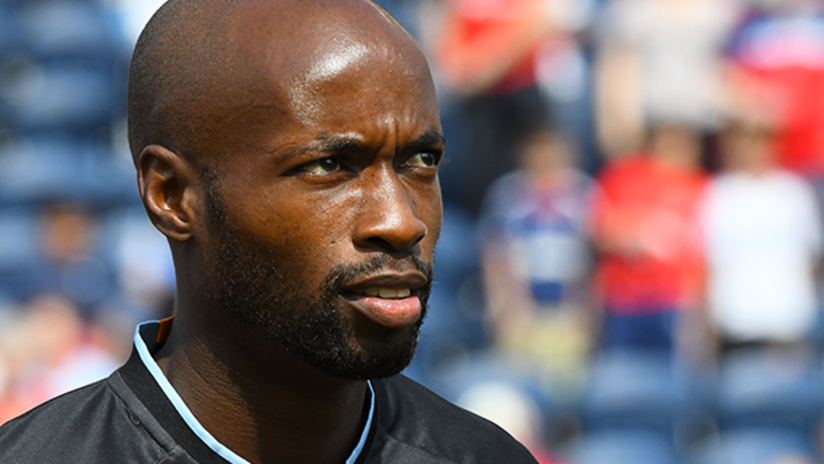

He’s not traditionally a big talker, and he’s never loved the spotlight. But when he’s in the mood, DaMarcus Beasley can tell you some stories.

There’s plenty to look back on and marvel at as the 37-year-old begins his post-playing career, who will be honored on Friday night for his contributions to the US men's national team at their Concacaf Nations League tilt against the Canada national team at Orlando's Exploria Stadium (7 pm ET | ESPN2, UniMas, TUDN, OneSoccer).

Quick, dogged and tenacious, he was one of Major League Soccer’s first young stars (watch his MLS highlight reel above) and first big outbound transfer sales, commanding a $2.4 million fee when he moved from the Chicago Fire to Dutch power PSV Eindhoven in 2004 at the age of 24. He played – and starred – in the UEFA Champions League (not to mention its Concacaf equivalent), the English Premier League and the Bundesliga, with the likes of Patrick Kluivert and Phillip Cocu for teammates, hoisting major trophies in multiple continents.

And there was his incredibly successful international career with the US men’s national team, during which he earned 126 caps across three different coaching regimes, won four Gold Cups and remains the only men’s player in program history to have played in four FIFA World Cups.

But what the man affectionately known as "Beaz" by his colleagues during his two decades in the game really wants to talk about is being back home, helping the potential DaMarcus Beasleys of tomorrow.

Pride of Fort Wayne

DaMarcus Beasley poses with local kids at a futsal court opening in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

“For us to get better and see talent sooner and to get our young kids playing at a higher level when they are 8, 9, 10 and 11 like they do in Europe,” said Beasley, “is actually doing the work, going out to the rural areas, going to the inner city, having scouts – but not just having scouts that say, ‘I’m doing this for a quick buck.’

“Because at the end of the day I would hope that every coach in this country, every scout, that their goal is one day to win a World Cup," he continued. "Yes, you want your kid to go and make a good living, make a lot of money. At the same time, the bigger picture is hopefully one day, those kids you’re coaching and developing can help the US national team win a World Cup. Because I want to be alive when it happens – I hope it does. But it starts from our youth, from smart people having better conversations, open conversations, and being open-minded about the youth in this country.”

Once Beasley finally empties out his locker for one last time in Houston this week his focus will shift swiftly toward that next chapter. And for the ageless wide man that likely means finally getting to spend a little more time at home – his true home, the humble setting of Fort Wayne, Indiana, where he was born and raised before the beautiful game whisked him away on a whirlwind world tour. And where he has for years operated a network of youth soccer camps that he once attended as a child, helped staff as a teenager and which now bear his own name.

“Fort Wayne loves him and appreciates him,” said Bobby Poursanidis, a longtime coach in Beaz’s neck of the woods who is his partner on the Beasley National Soccer School as well as the director of coaching at local club Fort Wayne United. “He wants to get more heavily involved now since he’s retiring, he wants to expand it to maybe do an overnight at a couple of the sites.

“He doesn’t aspire to be a coach,” Poursanidis added of Beasley, “but when he’s at the camps, he’s out there and I’ve got to pull him off. He’s out there teaching kids and showing kids and just providing them the experience, the understanding that he has, which is absolutely awesome … and he remembers names. He calls kids by name … he’ll sit at lunch with some of them and talk with them. He doesn’t need to do that. They already look at him as a rock star. But he does it.”

Inspiring the next generation

Beasley once embraced the look of a star, a committed lover of all things bling – “I had the diamond-encrusted No. 7, I had hoop earrings,” he remembers with a chuckle, “the diamond watches, the bracelets, all that. I kind of cringe at how I was” – “Run DMB” even founded his own jewelry store in Glasgow during his time with Scottish giants Rangers.

Yet he’s old enough to have experienced MLS’s threadbare early years, and occasionally reminds today’s young players how good they have it.

“You’ve got nutritionists now. I tell the guys: we didn’t have none of this stuff! Nutritionists? What’s that?” Beasley wisecracked. “The heart monitors, how much you run – ‘oh, you should kind of chill today because you ran a lot yesterday’ – huh?! … We didn’t have that back then! It was basically just you play until you fall out!”

No matter where life took them in the years since, DaMarcus and his older brother and role model Jamar – who also carved out a distinguished career, albeit with greater notoriety in the indoor game – always found a way to return to their unglamorous Midwest hometown, even if for only a few hours at a time, to connect with and perhaps inspire younger generations.

“They’d always come back and play indoor in the winter with us,” recalled Poursanidis, who’s known and coached the brothers since their early childhood – “DaMarcus was a scrawny little kid who loved the ball, he dribbled a lot more than passed,” he noted – and still plays golf with their father Henry. “They were so personal with everybody. They always made time for each and every person.”

When his playing schedule keeps him away, DMB – whose own daughter Lia, 5, may soon begin her own soccer career – makes sure to FaceTime with every weekly batch of kids who take part in his camps, modestly-priced affairs that emphasize fun and accessibility and take place in both the summer and winter months at nine locations across Indiana, Michigan and Ohio. He’s also part of a push to build futsal courts in the region’s urban areas.

“For me, I think it starts from conversations … I have schools in Ft. Wayne and in Michigan and Ohio – I’m not trying to say this is what we should do – let’s have a conversation," Beasley said.

Poursanidis proudly counts the Beasleys as two of five Fort Wayne locals to have played for the US national teams at one World Cup level or another. The tradition started with Nel Fettig, a US women’s youth international and WUSA pro in the 1990s and ‘00s, and continues today with US U-20 MNT prospect Akil Watts and Sky Blue FC veteran Sarah Killion – and there’s probably a sixth on the way in Amelia White, a striker who’s pursuing a spot on the US squad for next year’s FIFA U-17 Women’s World Cup.

Speaking up for the inner cities

Michelle Davies | The Journal Gazette, Fort Wayne, Ind.: Former U.S. World Cup player DaMarcus Beasley exchanges greetings with attendees at his soccer camp Dec. 28, 2018, at The Plex North in Fort Wayne, Ind.

Beasley’s experiences in the sport have made him keenly aware of how profoundly it can change lives around the world, especially in blue-collar communities like his hometown. And he doesn’t see enough of that in American soccer at large.

“Why isn’t there more people of color – Latino, yes, but more blacks – playing soccer? What are we missing?” he ponders. “Are we missing kids because they can’t afford it, they can’t play? Is that what the problem is?

“Do I think that we’re missing the boat in that aspect? Yeah, I do,” he added. “I don’t think that we put in the work to actually go out and find that sort of talent, because they don’t have the money. Everything in this country is about money, and it’s about having money to play soccer. Soccer should be free. You can go out to the street right now and get a 4v4 and go out and play. You shouldn’t have to pay for that. And it’s even a bigger problem in the inner cities.”

He’s encouraged by the rise of the new generation of young stars like Tyler Adams, Weston McKennie and Tim Weah. Yet he challenges the powers that be across the wider US soccer community to address the disconnect between American soccer’s traditionally suburban connotations and the black and brown kids who are often priced out of the game.

“They’re not spending time in the inner cities,” Beasley said. “It’s something that they need to revisit and something that needs to get better … if you want to play the game and you’re good at it, you’re talented, there should be someone there to watch you, to coach you and to push you in that right direction. And I think that kind of gets lost in the system, because we don’t have people that are willing to do the actual work.”

Beasley himself remembers the first time he sought to climb to a higher level in the sport, by trying out for the Olympic Development Program, once the nation’s primary talent-identification mechanism before the founding of the Development Academy and the MLS academy system we know today. He missed the cut for his state team in his own age level. Then he tried out for the next-oldest age group and was selected – putting him on the path to US U-17 stardom alongside Landon Donovan, Kyle Beckerman and the rest of their talented age cohort. And it nearly didn’t happen because of murky local youth soccer politics.

“People do things and think their way is the right way – and maybe it is, but have an open mind and listen to different ideas, avenues to push our younger players to get better,” he said, pointing to FC Dallas’ teenage Homegrown star Paxton Pomykal as a case study of what should be the norm, rather than an outlier.

“Even our team – why isn’t there a guy from the Houston Dynamo, a 17-, 18-year-old kid pushing through to our first team? What’s there? Why is it not happening?” he asked, highlighting Houston Homegrown Memo Rodriguez’s long road to meaningful MLS minutes. “Memo’s a great player. For me – obviously I’m biased – I think he should’ve got a shot a long time ago. But I see him every day in training; I’m biased. He’s just now starting to get his games, and he’s 23. In Europe, you’re considered old. Kids at 20, 21, you’re a full-time, playing 30 games a season.”

These topics shape his approach to his camps back home.

“We do have talent, not only here but across the state and across the region. [Beasley] does want to provide as many kids as he could the opportunity to play the game and not let the financial aspects of it get in the way. He does want to create a path,” said Poursanidis, noting that there’s a push to bring a USL franchise to Fort Wayne in the coming years to provide local kids with further opportunities.

Beasley isn’t sure what else the game has in store for him next. Though he insists he has no interest in professional coaching, he’s intrigued by a front-office role or perhaps television work. He’ll stay in Houston for the time being, and if his life to date is any indication, he’ll keep chipping away in the shadows, with no need for recognition or accolades, however deserved.

And of course, there’s Decision Day, one more matchday to savor for Run DMB, the quiet icon of American soccer.

“I just want to end how I began. That’s it. Just playing, trying to win a football match, respect the game, play the game in the right way,” he said. “I didn’t begin in the spotlight, I don’t want to end in the spotlight. Simple.”