Sporting Kansas City announced Monday morning that head coach Peter Vermes has signed a contract extension through 2023. It’s a well-deserved reward for Vermes. The former Kansas City Wizards and US national team player has been one of the most successful MLS managers in league history. He’s won four major trophies – three U.S. Open Cups and the 2013 MLS Cup – and Sporting have made the playoffs seven years in a row. He’s produced a rare blend of consistency and peaks. But beyond the raw totals, Vermes should be applauded for his evolution as a manager.

The success SKC have found under Vermes in 2018 – they rank first in the Western Conference through Week 10 – looks different than their conference-leading regular-season finish in 2011-12. Vermes teams of yesteryear were known for their pressing and intensity. They had moments of excellent soccer, but the backbone of the game plan was organization and overpowering energy. They kept things simple and executed well.

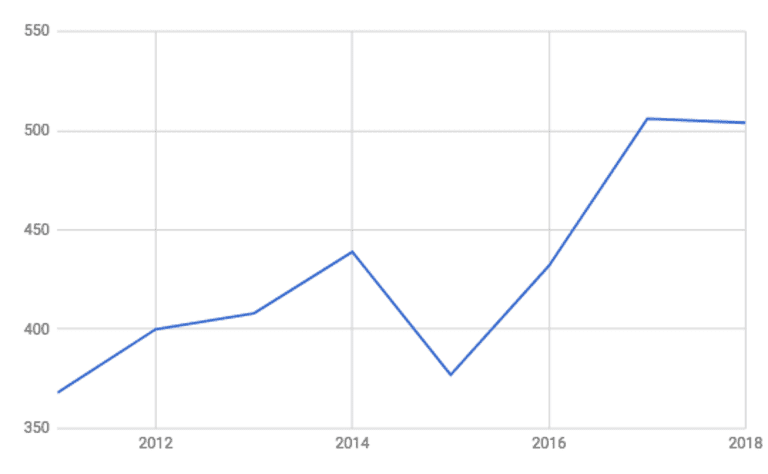

This year, Sporting have kept the defensive tenets and added attacking nuance. To provide (an admittedly crude measurement of) context, here are SKC’s passes per game, via Opta, tracked annually from 2011 through now:

Sporting KC passes per game, from 2011 through 2018

Note the clear upward trend over the last eight years. And it’s not only the passing that’s improved, but also the movement within the offense; that was evident over the weekend in Sporting’s game against Colorado.

Sporting right back Graham Zusi kept popping up in the middle of the field. It looked unnatural. A right back doesn’t usually get the ball there. Then the more I watched, I also noticed center mid Roger Espinoza showing up near the right sideline. Is that the center midfielder over near the benches?

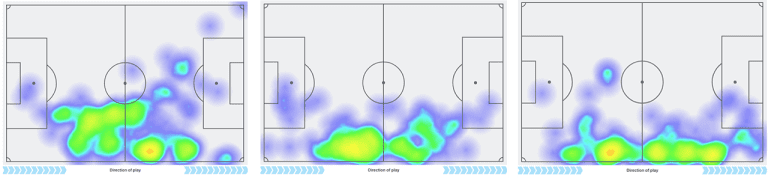

For reference, let's compare Zusi's Week 10 heat map – where his game actions took place – to that of two fellow attack-oriented right backs, Steven Beitashour (LAFC) and Auro Jr. (TOR). Look at how much more Zusi creeps toward the center circle.

Week 10 player position heat maps for Graham Zusi (left), Steven Beitashour (center) and Auro Jr. (right)

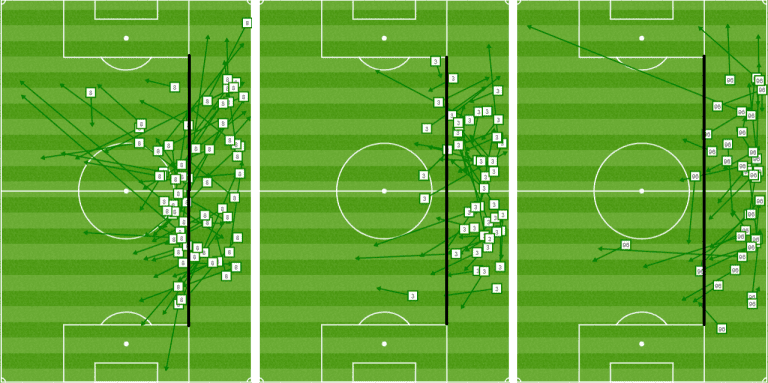

The same holds for Zusi’s passing chart in comparison to Beitashour’s and Auro’s (black line added for context):

Week 10 passing charts for Graham Zusi (left), Steven Beitashour (center) and Auro Jr. (right)

Notice how many more passes Zusi has in the central part of the field. Most outside backs receive the ball with their backs to the sideline, but Zusi gets a lower percentage of his touches up pinned against the sideline.

None of this was by accident. Zusi and Espinoza were working off of each other, along with whichever of SKC’s three forwards was on the right side with them. The players would move to a spot based on where the others were located. The players weren’t really playing positions; they were playing attacking zones.

Manchester City manager Pep Guardiola popularized the concept of offensive zones. Guardiola breaks the field into 20 zones for his teams. There are entire articles written on Pep’s practices, but the short story is that he doesn’t want two players in the same zone or vertical channel. If you’re in the same zone, then you don’t have proper spacing or aren’t providing a good angle for a pass.

Staggering the channels creates natural triangles. If you’re always thinking about your zone in relation to your that of your teammates, you’ll often be in good positions to attack. Good positioning leads to, well, what we see Manchester City do every week. Although it looks fluid and gorgeous, it’s all prepared and rehearsed. The fluidity arrives because the players have good spacing and angles.

Vermes hasn’t gone completely Pep, but Sporting have shown similar impressive rotations in a couple games recently. They first introduced it during their recent blowout of Vancouver, particularly on the right side of the field. Vancouver went down to nine players 40 minutes into the game, which diverted the conversation, but the movements came back again this weekend against Colorado.

Espinoza, Zusi and right winger Johnny Russell each worked off the other’s positioning. They had their given starting positions, but they were more concerned with their zones than their named position. Russell would generally take the widest channel, Zusi the next inner channel, and Espinoza the most central spot of the three. But if a player would ever switch zones or channels, a different player would fill in; it was constantly fluid and unpredictable.

It’s common for teams to have a systematic two-man rotation on the wing. When the winger tucks in, the outside back overlaps to take the wide channel. SKC really differentiated by adding the third congruous player, center midfielder Espinoza.

When Espinoza would move wide to find space, Zusi would vacate the channel and move to the center mid spot. When Russell would move centrally to find the ball, Zusi would slide farther outside or overlap down the side. Except, sometimes when Russell would move centrally, Zusi would actually maintain his spot 10 yards in from the sideline and Espinoza would shift to the sideline. At different points in the game, Zusi, the nominal right back, looked like he could be playing center mid or winger; Espinoza, the center mid, looked like he could be playing outside back.

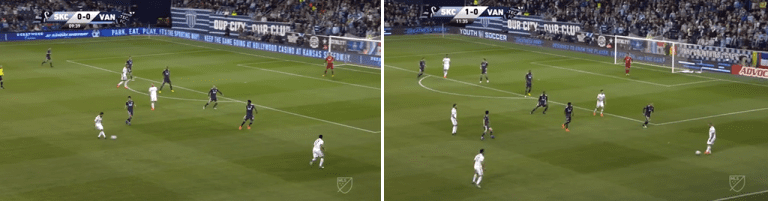

Watch Zusi, Espinoza, and (in this case) Daniel Salloi react off each other’s positions:

Zusi starts farthest to the touchline, Espinoza one zone more central, and Salloi adjacent to that. As the play progresses, Zusi moves toward the middle of the field and Salloi, seeing Zusi’s movement, takes over his wide channel.

Similarly, here are two images from SKC’s game against Vancouver, showing the shifted positions:

Left: Russell is central, Zusi in between, Espinoza making the wide run; Right: Zusi is central, Espinoza between, Russell out wide

It helps Sporting that Zusi used to play center mid and Espinoza spent time at outside back for Wigan in England. Not all teams could ask players to switch so flawlessly.

It’s not the type of action that totally changes a team's outlook, but it’s the type of movements that A) show a team is on the same page; and B) provides the layer of complexity that separates mediocre teams from good teams. When a team adds an offensive wrinkle, as SKC have, it makes reading the situation more difficult. Defenders don't expect to see an the outside back receive the ball on the half turn in the middle. In the moment, this can add a vital second of reaction time.

Sporting’s adjustment isn’t rocket science. But it’s a touch more complicated than most teams seem willing to take on. It shows a deeper level of thinking and implementation. We knew we could always rely on Vermes to produce an organized team that would compete, and now we see Sporting teams that can possess and attack as well as anyone. The goal-scoring feats this year aren’t random.

If we thought we had Peter Vermes figured out, it's time to reevaluate that perception. It’s always been fun to watch Vermes teams, but it’s been even better to see him grow as a coach.