CHESTER, Pa. – A couple of years ago, Ennis Stewart, the son of former US international Earnie Stewart, popped in a DVD and began watching one of the most memorable goals in American soccer history.

With the wide-eyed exuberance and curiosity of an 11-year-old, he leaned in close to study the terrific buildup, from Thomas Dooley’s composed touch and turn in the middle of the field … to Eric Wynalda’s slicing run and pinpoint pass out wide … to Tab Ramos’ deft dribbles, defense-splitting vision and chip toward the box.

Just then, the boy’s father flashed onto the screen, making a diagonal run between defenders to collect Ramos’ pass and dink the ball past the goalkeeper to score the game-winning goal in the US national team’s historic 2-1 upset of Colombia in the 1994 World Cup – the Americans’ first World Cup victory since 1950.

Young Ennis, who was born shortly before Earnie played in his final World Cup in 2002, smiled. And noticing that his father had come into the room, he asked if they could watch together.

Perhaps this could have been an opportune father-son moment, a chance for Earnie to sit Ennis on his lap and tell him about the spirit of underdogs, about how those 1994 and 2002 US teams shocked just about everyone to advance to the knockout round, about how anything is possible if you just put your mind to it.

Or …

“I just walked by,” the elder Stewart remembers.

The former US national team midfielder never misses a chance to bond with his children – Ennis is now 13 and his daughter, Quinty, is 16 – but that goal vs. Colombia, it turns out, is something that he doesn’t like to watch. In fact, he actively avoids it. Same goes for the ’02 World Cup or any of his other USMNT appearances in which he scored 17 times in a decorated international career from 1990 to 2004. Or, for that matter, anything that involved him as a player or an executive, a post he recently assumed on these shores after spending the last 10 years in his birthplace of the Netherlands.

“I don’t like looking at myself,” he tells MLSsoccer.com in his office at Talen Energy Stadium (formerly PPL Park), a few days after he was officially introduced as the Philadelphia Union’s sporting director. “Once I see myself on TV, no matter it being an interview [or playing], I just don’t like it because I see all the negative things.

- MEET EARNIE STEWART: Former USMNT star's path from playing to management

“I don’t want to call myself a perfectionist because it sounds so stupid. But I find it very, very difficult to find the positive things in myself and I always see the negative things. It bugs me.”

There’s more to it than that, though. For the ambitious Stewart, it seems there’s no sense looking behind when there’s still so much to do in the future. And while the 46-year-old has often defied expectations, from leading the USMNT to two surprising World Cup runs to assembling strong teams with a limited budget as a savvy front-office executive, he’s never considered his success a surprise worthy of nostalgic remembrance.

It’s just something he found a way to do. And there’s still more work to be done.

“Having played as a professional or having made it to the national team or having played in the World Cup, you don’t do that if you think, ‘I’m the underdog and might lose this,’” says Mike Sorber, a Union assistant coach and a teammate of Stewart on the ’94 World Cup team. “You make it because you think, ‘It doesn’t matter what the challenge is. I’ll find a solution.’”

Now comes the next big challenge: can Earnie Stewart help the Philadelphia Union build a foundation for future success after years of instability?

Earnie Stewart and Landon Donovan embrace following the US national team's famous Round of 16 victory against Mexico at the 2002 World Cup in Jeonju, South Korea. Stewart's 101 caps rank 14th in USMNT history. He also scored 17 goals and added 10 assists during an international career that spanned 14 years and included three World Cup appearances (1994, 1998, 2002). Photo via Reuters

IF IT WERE UP TO Earnie Stewart Sr., his son would have played a different kind of football.

Growing up in Texas, the elder Stewart was a high school football player in the (American) football-crazed state and a diehard Dallas Cowboys fan. (“I’m sick to death they’re not winning,” he says.) That never changed, even after he joined the U.S. Air Force at the age of 18 and was deployed to the Netherlands, where he married a Dutch woman, raised a family and has spent the majority of his time ever since.

“To be truthful about everything, I love American football,” he says by phone from the Netherlands. “When Earnie was born, I always dreamed of him being a wide receiver or a quarterback.”

It didn’t take long, though, for the elder Stewart to realize that his son had an affinity for Holland’s most popular sport – the other football. And he saw that he had the speed and determination to make it, too.

“I remember a few times when the weather was bad, they’d call up and say, ‘Hey, the game’s been rained out. Nobody’s playing today,’” Earnie Stewart Sr. recalls. “But Earnie would get on his bike and ride down in the cold and try to find a pickup game.”

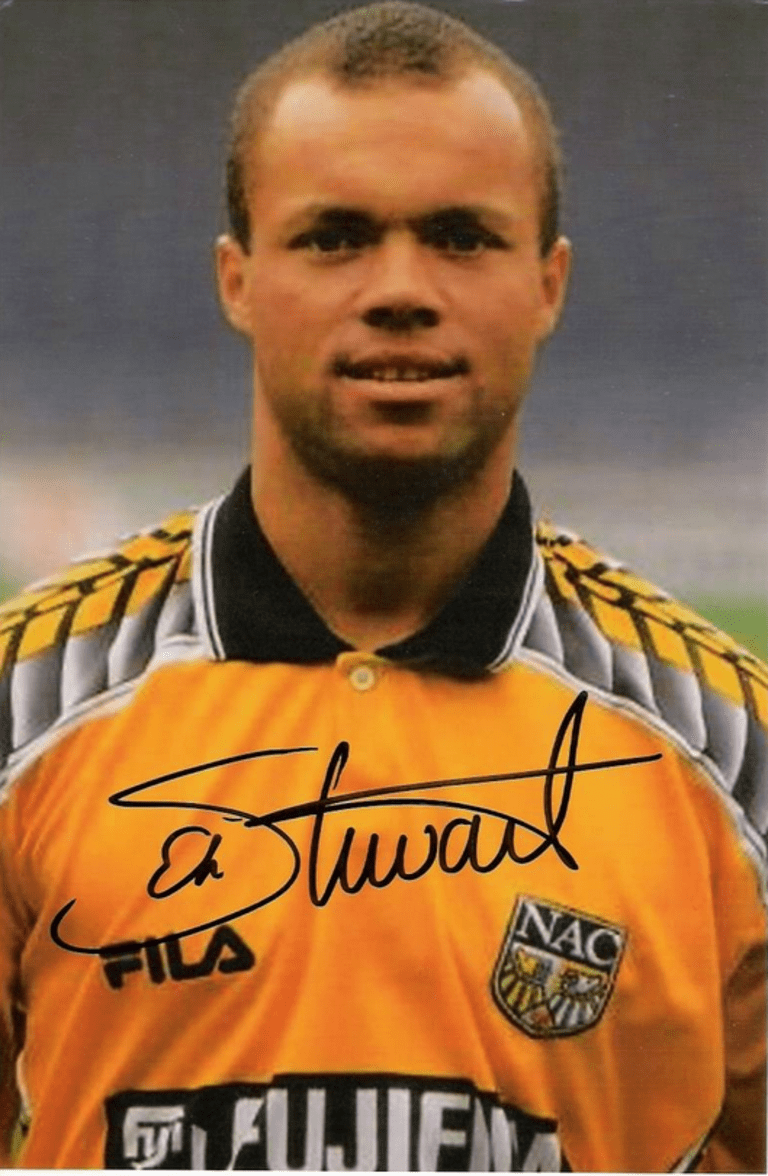

Stewart made 199 appearances for NAC Breda from 1996-2003, scoring 50 goals for the club. He also played for VV-Venlo and Willem II in the Netherlands.

According to his father, young Earnie was initially used as a defender in youth leagues. But when one coach moved him up top as an 11-year-old, he scored 10 goals in one game and “that was when he got rolling.”

Stewart began his professional career as a teenager with VVV-Venlo, before later playing for Dutch clubs Willem II and NAC Breda, scoring 114 goals in 16 years between the three clubs.

And he was only 21 years old when he first joined the US national team in 1990 – the ultimate dream for a kid who adapted to Dutch culture but always felt connected to his American roots as well.

“All I wanted to do was play for a national team, not knowing which one that would be,” says Stewart, adding that he was first invited to a Netherlands camp but didn’t make the final cut. “The United States is such a big and powerful country that you felt a couple of feet taller when you played for the national team and got to wear that jersey.”

Stewart would go on to be a stalwart for the US and was one of the team’s rocks during 2002 World Cup qualifying, during which he scored eight goals and wore the captain’s armband for several games. But it was that first World Cup in 1994 that was especially meaningful to Stewart’s father, who once imagined his own fate might include college football glory in the Rose Bowl.

- MEET EARNIE STEWART: Hear what former AZ exec has in plan for Philly

Instead, he was in the stands to watch his son score the game-winning goal against Colombia in the historic California stadium.

“I had always dreamed of coming out of the tunnel myself,” says the elder Stewart, who spent 21 years in the Air Force and now works as a manager in a Dutch store that sells goods to US serviceman. “But when I saw him coming out of the tunnel at the World Cup, I was so proud of him.”

For the younger Stewart, the entire ’94 World Cup remains a blur – one that hasn’t come into any more focus in later years since he doesn’t watch the highlights. But his first World Cup was certainly special, and he does have at least one clear recollection from the goal that helped the Americans knock off heavily favored Colombia and move into the next round of the watershed tournament.

“I remember there was a pile and I couldn’t get any air on the bottom of that pile and it was so tremendously hot,” he says. “And the day after I remember doing my laundry. That’s pretty much it.”

After beginning his post-playing career in 2005 as VV-Venlo's technical director, Stewart joined AZ Alkmaar in 2010 following a stint with NAC Breda. During his five-plus years with the Cheese Farmers, AZ regularly punched above their weight, challenging Dutch heavyweights PSV, Ajax and Feyenoord in the Eredivisie and consistently qualifying for the Europa League. Photo via AZ Alkmaar

THERE'S A SCENE in the 2011 film Moneyball in which a group of scouts, stereotypical baseball old-timers, describe prospects in almost comically qualitative terms – “baseball bodies” and “eye-candy tests.”

Billy Beane, the Oakland Athletic general manager for whom the movie and 2003 Michael Lewis book of the same name is based, responds with disgust, “You guys are sitting around talking the same old good-body nonsense like we’re selling jeans, like we’re looking for Fabio. We’ve got to think differently.”

In other words, the A’s needed to stop looking at superficial attributes and find underappreciated and undervalued players in order to compete.

It was in his last job as the director of football affairs at Dutch top-flight club AZ Alkmaar that Stewart took other members of his front office to see Moneyball, hoping to bring that general philosophy to a team that, like the A’s, didn’t have the same size budget as their domestic competitors.

“You learn to be creative,” Stewart said in an ESPN.com feature from Jan. 2012 that first chronicled his affinity for Moneyball. But it took some time to build a new scouting database and get the right people on board to help with the Moneyball plan. Eventually, former Dutch Major Leaguer Robert Eenhoorn joined the club as general director in 2014, and Beane himself became an AZ Alkmaar advisor in March 2015.

Among Stewart's success stories at AZ Alkmaar was the signing of fellow American Jozy Altidore. The forward scored 50 goals in all competitions before being sold to Sunderland. (Courtesy of AZ)

The hires – two baseball men breaking down barriers in the beautiful game – were unconventional, to say the least.

“Soccer is a very conservative sport in Europe but we were known to be a club of innovation,” said Stewart, who played baseball while growing up in Holland before turning to soccer. “In the beginning, people were skeptical. They still are. But once you believe in something, you have to follow that path.”

Stewart noted that translating Moneyball, which focuses on qualitative evaluation to minimize bias, from baseball to soccer wasn’t difficult because “numbers are numbers.” The key, like it was for the A’s, was simply focusing on certain statistics to uncover overlooked players and bridge the financial divide.

And he, too, didn’t care about how those players looked in a pair of Levi’s.

“A lot of times when you look at a player, you already have a clouded vision of him,” Stewart says. “You like him or you don’t like him because, I don’t know, he’s athletic or he’s not athletic. And you have to try to look past that when it comes to the scouting process. What numbers do and what analytics do is they don’t look at who the person is – if he’s athletic, what kind of ethnicity he is. It’s just the numbers. These are the facts.”

It’s no secret this philosophy is one of the main reasons why Stewart was hired by the Union. Majority owner Jay Sugarman has spoken openly about exploiting different edges to get a leg up on the competition and when he saw Stewart had worked with Beane, he remembers thinking, “Ah, common soul.”

What also set Stewart apart from other candidate in the club’s year-long search to find their first sporting director is his approach to player development, which will be central to his job as he also oversees the Union’s youth academy and USL affiliate, Bethlehem Steel FC.

And that, Stewart said, “has nothing to do with analytics.” It’s simply about helping players grow by getting to know them, on and off the field.

“First and foremost, there’s a mistake we make in soccer a lot of times,” Stewart says. “When we look at players, we look at them as only professionals, like they have no private lives at all. We never discuss that. We never talk about that.

The Union hope Stewart, pictured here at his introductory press conference, can help them return to the playoffs for the first time since 2011. (courtesy of the Philadelphia Union)

“It’s just getting to know players beyond the soccer player. What is his background? What drives him? What kind of ambition does he have? Together you can make a plan on going forward and getting the best out of this player. I truly believe there’s more to a player than having them come into practice and leaving after practice.”

Player development has certainly been a challenge for the Union, who have had only one Homegrown signing – Zach Pfeffer, traded to the Colorado Rapids following last week’s SuperDraft – see significant playing time while others such as Jimmy McLaughlin and Cristhian Hernandez failed to crack the first team and were eventually waived.

And as the Union’s youth academy at YSC Sports continues to grow, Stewart understands the foundation has to come from Homegrown talent and that properly developing those players could at least partially cure the franchise’s costly roster turnover year after year.

But in the short term, after the Union traded away or declined options on more than a dozen players following a disappointing 2015 campaign, there will be plenty of roster changes as the club has money, flexibility and an ever-improving scouting database to scour the globe for signings that can help the team win in 2016 and beyond.

And Stewart knows there are potentially players to be found in every pocket of the world, perhaps ones that are sometimes forgotten, perhaps ones who can help the Union develop a new reputation.

Earnie Stewart celebrates D.C. United's 2-0 victory against the MetroStars at Giants Stadium following the first leg of the 2004 Eastern Conference semifinals. The Dutch-born midfielder scored the opening goal in the match, and would go on to lift MLS Cup in his second and final season in MLS. Photo via Getty Images

EARNIE STEWART WAS ANGRY. It was Sept. 4, 2004, and D.C. United had just lost 3-1 to the Chicago Fire at Solider Field, dropping their record to 6-9-9 in what was shaping up to be a underachieving season.

What was said in the D.C. United locker room that day in 2004 remains a mystery. Perhaps it’s not appropriate for print. Or perhaps the passing of time has dulled the memories of those involved.

But this much we know: Stewart and teammate Ryan Nelsen gave a rousing speech. And from that point forward, D.C. United became a dominant force that went on to capture the 2004 MLS Cup.

“I remember the tone of it and I remember after that we went on [a great run],” recalls Josh Gros, now the Union’s team coordinator and a rookie on the 2004 D.C. United team. “That was the turning point.”

Stewart and Freddy Adu share a moment while teammates with D.C. United in 2004. Adu was a much-hyped 14-year-old MLS rookie that season, which would end with the Black and Red lifting MLS Cup. (courtesy of Getty Images)

D.C. would go on to win eight of 10 on their way to MLS Cup glory, a regular season loss in Columbus and Eastern Conference Final decided by penalty kicks the only remaining blemishes on their record.

By then, Stewart was a hardened veteran with weak knees. He didn’t score much during the 2003 and 2004 seasons with D.C. United – his only two in MLS – but he emerged a leader, counseling young players like Union midfielder Brian Carroll and Gros, who roomed with Stewart on his first West Coast trip.

Gros, of course, idolized the three-time World Cup veteran and wasn’t surprised by Stewart’s effective midseason speech because “he was someone that had the respect of the entire team.” And despite his reluctance to revisit the past, Stewart still calls that locker-room talk a “defining moment.”

“It was kind of like all of a sudden it was normal we became champions,” he says, “because of the thought that we had of who we were and what our goal was.”

In many ways, puffing on victory cigars after D.C.’s 3-2 win over the Kansas City Wizards in the 2004 MLS Cup proved to be a fitting swan song to Stewart’s professional career and a perfect transition to the next phase of his life.

He tried to keep his career going with his first club, VVV-Venlo, but the cartilage in his right knee gave out in 2005. Perhaps that was a blessing in disguise. Stewart was quickly named the club’s technical director instead of running their youth academy as initially planned.

“Who knows? Maybe if I would have played on, I wouldn’t be sitting here,” he says. “I don’t know what life would have been like. Maybe I would have. But the opportunity arose right away to be a technical director in Holland so I count my blessings for that.”

Stewart had immediate success in the front office, first at VVV and then at NAC Breda, stints that led to a job with AZ Alkmaar in 2010. It was there he really made his mark as the club rose up the Dutch Eredivisie table and became a fixture in the Europa League while simultaneously slashing its payroll.

“I’ve never looked at it as I’ve been at clubs with a lesser budget,” says Stewart, who admitted in his first Union press conference that it was always his ambition to return to the United States. “Even if I had been at Ajax, PSV [Eindhoven] or Feyenoord, my budget would have been less than Chelsea. That’s not the drive that I have. To bring out the best in people, that is something I do have. And the budget really doesn’t make a difference in that.”

That kind of thinking will certainly be beneficial as Stewart’s now in charge of a Union franchise that will not shell out the same kind of dollars as MLS’s biggest clubs. And Stewart admits that he and his staff – including two Philly natives, head coach Jim Curtin and technical director Chris Albright – are “not going to build Rome in a day” as they look to set a foundation for long-term success.

Stewart and Union head coach Jim Curtin pose with first-round SuperDraft pick Joshua Yaro in Baltimore. Philadelphia had three picks in the top six. (courtesy of Major League Soccer)

Stewart began to lay the groundwork for that foundation last week in Baltimore, working the phones to end up with three of the top six SuperDraft picks, which Philly used to primarily bolster their leaky defense by nabbing Georgetown defenders Joshua Yaro and Keegan Rosenberry (just a day after they took a flyer on Brazilian second-divisioner Anderson Conceição, who Stewart described as a central defender with a “great left foot”). The Union also selected one of college’s premier goalscorers in Creighton’s Fabian Herbers, who could compete for time on the wing with two other offseason additions: former D.C. United stalwart Chris Pontius and New York Cosmos import Walter Restrepo.

The Union, of course, still have other offensive needs heading into training camp and could probably use a veteran presence on the backline if they move Maurice Edu into the midfield. But no matter the obstacles for the team (which has only made the playoffs once in six years) and for himself (he admittedly still has a lot to learn about MLS), Stewart will not go into the first game of the 2016 season this March feeling like an underdog.

No, he’ll have high expectations from the very beginning. Just like when he was on the US national team and he went toe-to-toe with world powers like Brazil. Just like when he decided one day that the 2004 D.C. United team was better than they had been playing. Just like when he put AZ Alkmaar in a position to beat Dutch powers Ajax, PSV and Feyenoord by being smart and innovative.

Just like always.

“I never go in looking at it like we’re the underdog,” Stewart said. “I want to get the best out of players. I want to get the best out of my staff and the team we have and win games. It could be that you have less money. It could be that you have less this or less that.

“But if you keep looking at that and worrying about that, you’re never going to go anywhere.”

Dave Zeitlin covers the Union for MLSsoccer.com. Email him at djzeitlin@gmail.com.

THE WORD is MLSsoccer.com's regular long-form series focusing on the biggest topics and most intriguing personalities in North American soccer. Check out THE WORD archive.