In 1992, the United States' top professional club at the time, the San Francisco Bay Blackhawks, traveled to Mexico City to face the legendary Mexican side Club América in a home-and-away series at the most fearsome venue in North American soccer: Estadio Azteca.

Located on the high plateau just outside Mexico City, the Azteca stands 7,300 feet above sea level. By comparison, Denver, Colorado, the "Mile High City," sits some 2,000 feet lower.

No amount of training, even at altitude, can adequately prepare you to play on its hallowed field.

"I was probably in the best shape of my life by far," recalled Blackhawks and future MLS defender Mark Semioli. "I was 25 years old. I was the perfect age. It felt like I couldn't even move my legs from the get go. It was as if you smoked 100 cigarettes before the game because the altitude was still strong, but the smog was incredible."

Yet despite the altitude and the elements and the hostile crowd, the Blackhawks took that Hugo Sánchez-led América to the brink of elimination in the CONCACAF Champions' Cup (the ancestor of the CONCACAF Champions League).

Since then, no professional club team from either Canada or the United States has traveled to Azteca to play against América in international competition.

That all changes on Wednesday, when the Montreal Impact face Mexico's most successful team in the first leg of the CCL final (9 pm ET; FOX Sports 2, UniMás in USA; Sportsnet World, TVA Sports in Canada).

From the moment they were formed in 1988, the San Francisco Bay Blackhawks signaled their intent to become the biggest and best professional soccer team in America. The club's owner, Bay Area real estate mogul Dan Van Voorhis, spared no expense in providing the team with the best coaches, trainers and travel possible.

When the San Francisco Chronicle asked him why he would risk so much of his own money on a niche sport like soccer, Van Voorhis replied, "I like to work with creative people and I like challenges. Soccer and the Blackhawks certainly present all those to me."

The ambition of the club was evident from the beginning. At a time when many American professional soccer players were struggling to make ends meet, Van Voorhis treated his players like kings, flying them in his private plane, treating them to extravagant meals and putting them up in the finest hotels.

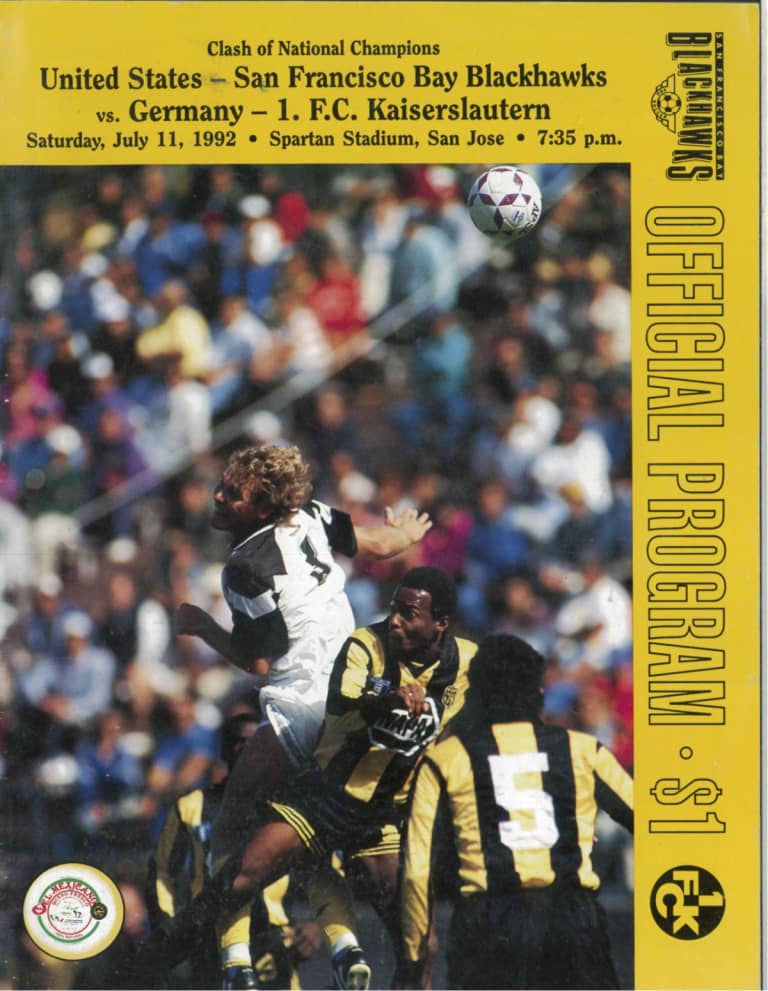

Van Voorhis's lavish spending helped the Blackhawks lure the most talented American players to the Bay Area. From 1989 until the club's final season in 1993, the Blackhawks were home to some of the greatest American players of that era: Eric Wynalda, Marcelo Balboa, John Doyle (pictured right, on a Blackhawks program), Dominic Kinnear, Troy Dayak and Paul Bravo.

Arriving at a tumultuous time in US pro soccer, the Blackhawks competed in an alphabet soup of different leagues over their short existence, including the Western Soccer League, the American Professional Soccer League and the United States Interregional Soccer League (the forerunner of today's USL). But they always ran at the front of the pack.

Between 1989 and 1991, the Blackhawks played in three championships in a row, winning two of them. The last of those championships, the 1991 APSL title, qualified the Blackhawks for a place in the 1992 CONCACAF Champions' Cup.

In international competition for the first time in their history, the Blackhawks believed they could become the first American team to win the entire tournament.

"We had the expectation that we would go far in this thing," said Semioli, who later spent six seasons in MLS with the LA Galaxy and the MetroStars. "We had real plans to win it, and the focus from [Van Voorhis] down was, 'We're going to take this thing.'"

The Blackhawks cruised through the first three rounds of the tournament. They defeated opponents from Panama, Belize and Honduras by a staggering aggregate score of 22-2. All that stood between them and a place in the finals was an eight-time Primera Division and three-time Champions' Cup winner: Club América.

The Blackhawks entered Azteca with a plan. Through 60 minutes of play, it looked like it might actually work. As the Impact did against Costa Rican opponents Alajuelense in this year's semifinal, the Blackhawks played compactly on defense and cautiously ventured forward on the counter.

Semioli explained that his entire job that day was to shadow América's Mexican international midfielder, Luis Roberto Alves. By his own estimation, Semioli didn't cross the midfield line more than five times in the match.

Still, the defensive strategy appeared to pay off. At halftime, the teams left the field deadlocked at zero.

While América got on the scoreboard first in the 47th minute, less than seven minutes later, Jamaican international Peter Isaacs improbably equalized for the visitors. Once again, the teams were even, and the Blackhawks could feel the mood inside the stadium change.

Then disaster struck.

In the 64th minute, Blackhawks defender Troy Dayak (pictured right, with the Earthquakes) was given a straight red card for punching Mexican forward Hugo Sánchez – then recently returned from Real Madrid – in an off-ball incident that was caught not only by the assistant referee, but also by every camera in the stadium.

"We in the United States were so accustomed to bad refereeing and no media coverage at all – you think you can get away with almost anything. But not at Azteca Stadium," said former Blackhawks midfielder and captain Derek Van Rheenen.

Dayak describes that red card as one of the defining moments in his career.

"I was playing in a huge stadium in a massive environment," Dayak remembered. "I was doing my job, specifically to mark out their best player, and I was doing that. And the guy found a way to win the game for his team by getting me thrown out."

According to Dayak, who played through the match with a broken bone in his ankle, Sánchez repeatedly targeted his foot and ankle with off-ball challenges that went ignored by the referee. After Sánchez punched Dayak in the solar plexus, Dayak instinctively swung out. As so often happens, the referee only saw the second punch.

The red card forced an exhausted and demoralized 10-man Blackhawks squad into emergency defending all over the pitch. Within 15 minutes of Dayak's dismissal, Sánchez, who would later star in Major League Soccer's inaugural season with the Dallas Burn (now FC Dallas), scored two goals that left the Blackhawks gasping for breath.

Dayak, meanwhile, sat dejectedly in the bowels of the stadium, a sterile, concrete locker room that he described as "the belly of the beast," where he could only listen in horror to the rumble of the crowd above and the stadium loudspeaker blaring the calls: "Goooool! Hugo Sánchez!"

"We were in great shape after Peter's goal," Blackhawks coach Laurie Calloway told the media after the game. "But once we lost Troy [Dayak], who we thought kept Sánchez under wraps until then, we had a lot of trouble defending."

Part of that stemmed from Dayak's dismissal, but the majority stemmed from a combination of fatigue and América's distinctive home-field advantage.

"Azteca was very hot and a huge field," said Semioli (pictured left, behind Sánchez). "It's kind of a spread-out game, and teams [like América] that can possess the ball can run you ragged, much as they did to us."

No Blackhawks player, however fit or fresh, was immune to the debilitating effects of the altitude.

"I don't know how those guys played 90 minutes, because after 20 minutes I felt like there were arrows stuck in both of my lungs," said forward John Garvey, who came into the first leg as a late substitute. "I couldn't breathe. It was just such an advantage. It was the most uncomfortable feeling, that pollution and altitude."

Despite the loss, the Blackhawks were in an optimistic mood heading into the second leg. They would be playing at home and needed just a 2-0 scoreline to push the series to extra time. If they could shut Sánchez out of the game, they thought, they would have a chance.

Like their opponents, the Blackhawks possessed a home-field advantage of their own: the narrow confines of San Jose State University's Spartan Stadium.

"When teams came to play on that field, we were very used to it: being in very tight confines, how to play smart on that field, how to move the ball around [on] the fast turf that it had," said Semioli. "We felt pretty confident that this would lend itself to a tremendous advantage, even over a highly skilled Mexican team, because we knew how to work the field to our advantage."

That confidence bore immediate dividends when, in just the sixth minute of the match, forward Joey Leonetti headed a Lawrence Lozzano cross beyond the reach of América goalkeeper Alejandro Garcia.

But in the 27th minute, Blackhawks goalkeeper Mark Dougherty tripped midfielder Alves inside the box. Sánchez, who had been kept quiet by Semioli, stepped up and buried the penalty. Like that, the game was even.

"There was contact," Dougherty, who later played for MLS' Tampa Bay Mutiny and Columbus Crew, said of the foul after the match. "But not enough to warrant a penalty."

Despite their howls of protest, the Blackhawks pressed on. Their perseverance paid off as fullback Tim Martin – a starter for MLS' San Jose Clash (now Earthquakes) from 1996-98 – scored with a right-footed blast from well outside the box.

For the second time in the match, the Blackhawks found themselves needing just a goal to send the series to extra time, and in the 63rd minute, it looked as if they had found it. Leonetti took the ball to the endline and crossed to an unmarked Townsend Qin at the far post.

As the players ran over to celebrate with Qin, they turned and saw that the assistant referee had raised his flag. Offside.

While it sounds as if the Blackhawks had been “CONCACAF'd” – Semioli admitted that the team thought that there was a conspiracy to keep them out of the final – the assistant referee responsible for the call was American.

Without Qin's goal, though, the 2-1 scoreline was not enough for the Blackhawks to advance to the next round of the tournament.

The next morning, the San Jose Mercury News led its story this way: "Defender Mark Semioli can tell his children some day that he shut down one of the world's legendary strikers, Hugo Sánchez. The rest of the San Francisco Bay Blackhawks can tell their grandchildren that they defeated one of the world's internationally recognized teams, Club América.

"By then, maybe, it won't hurt as much to admit that none of it mattered."

But for the players that traveled to Mexico City, the experience of playing at Azteca, the very ground where Pele and Maradona made World Cup history, is one they still vividly remember more than 20 years later.

"It was just incredible, the venue," said Garvey. "There were two World Cup finals there. And when people ask me where I played, I always say I played at Azteca."