THE WORD is MLSsoccer.com's weekly long-form series. This week, writer Charles Boehm examines the steady rise of Sunil Gulati from a youth assistant soccer coach in Connecticut to his role as the head of U.S. Soccer, and the challenge that awaits him with his recent election to FIFA's Executive Committee.

Panama City, Panama, was founded some 500 years ago by Spanish conquistadors. As a base for their expeditions into the interior of the New World, it served as a transshipment point for untold tons of gold, silver and other treasure plundered from the Inca Empire.

Whether any of the emissaries at CONCACAF's XXVIII Ordinary Congress in April knew that history is unknown. But it provided an interesting backdrop when they gathered at the Westin Playa Bonita, a posh beachside hotel near the southern entrance to the Panama Canal, to take part in elections for several executive positions, most notably the region's representative to the most powerful body of international soccer governance: the FIFA Executive Committee.

Comprising 24 members from across the globe, the “ExCo” is the most exclusive collection of the game's illuminati, the group that charts FIFA's course and, until very recently, decided everything of consequence about World Cup tournaments. Holding a seat on the ExCo provides the seat-holder – and, by extension, his confederation and even his national federation – a voice in the conversation taking place at the highest echelons of the game.

On this day in April, CONCACAF was staging its first contested ExCo election in many years. The long reign of Trinidadian power broker Jack Warner had come to an embarrassing end amid charges of corruption and mismanagement, and the duel to replace him was primed to be a doozy as U.S. Soccer Federation president Sunil Gulati squared off against his Mexican counterpart, Justino Compeán. It was a clash of the region's heavyweight nations.

The election would be decided via public vote, as each of the 35 delegates from every member of the confederation would stand and tell the world whom they'd selected.

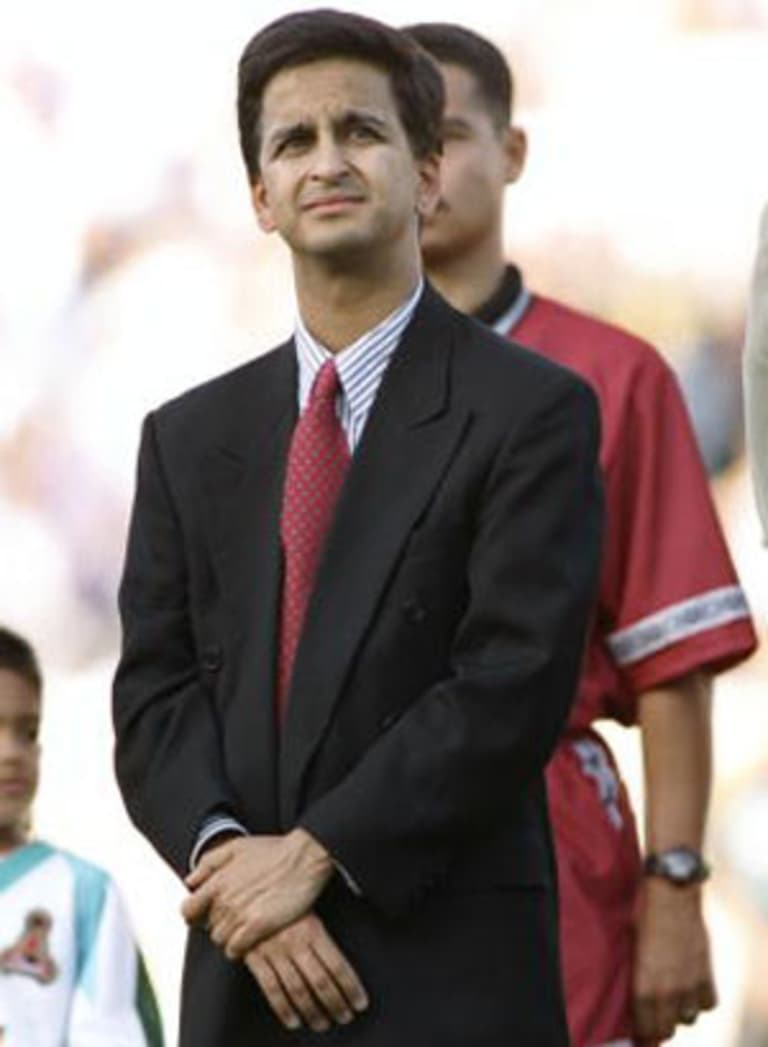

US Soccer Federation president Sunil Gulati says he expected a close vote to be elected to the FIFA Executive Committee but not as close as it turned out. Says Gulati: "It was a pretty intense period of time." (USA Today Sports)

“CONCACAF hasn't had many elections in the last decade or so, so this was an interesting experience, and one that came down to literally the last vote,” Gulati says. “It's a public vote, which changes the nature of some things. It was a relatively short but pretty intense campaign.”

The winner needed at least 18 votes to win, and going in, Gulati thought he'd rounded up 20. But UNCAF, the Central American sub-confederation, voted as a bloc for Compeán, and the Mexican also managed to peel off several of the small but numerous Caribbean nations – including US territory Puerto Rico.

After 34 voters had stood up and announced their vote, the race was deadlocked at 17 votes apiece. The entire election suddenly came down to the final vote, to be cast by the rep from Anguilla, a 35-square-mile, British-owned island in the Caribbean with some 15,000 residents.

“It was a pretty intense period of time," Gulati recalls. "The last day, the last couple of hours – the last 60 seconds, since it came down to the final vote out of 35 – in a public vote where every person is standing up after the other and saying who they are voting for, was pretty intense.”

All the tension broke when the Anguillan representative stood and declared his vote for Gulati, instantly making the soft-spoken Columbia University economics professor one of the most powerful people in world soccer.

That outcome was a decidedly fateful one for the future of soccer in the United States. Armed with ferocious intelligence and lessons learned from a long, methodical climb from part-time youth coach in suburban Connecticut to the very summit of the U.S. Soccer pyramid, Gulati is about to take on the biggest challenge of his career.

* * *

Born in Allahabad, India, to a family that emigrated to the US when he was five, Gulati's connection to the game runs back to his own childhood, and his involvement in the executive side of it goes back nearly as far.

He was a coach, referee and a player as a kid, and says he got involved in the administration side of soccer simply because he and his friends wanted to play, and there was no team in their age group. By the time he was 21 he was an assistant coach with an elite-level youth team in Connecticut, and he was an administrator for the program at 22.

That’s roughly when Bob Gansler first met the man he calls “the prodigal son.” Gansler, who would go on to become the US national team coach at the 1990 World Cup, remembers how Gulati steadily climbed the administrative ranks of U.S. Soccer during Werner Fricker's presidency. At a time, the federation possessed a mere fraction of its current wealth, size and power, and being involved meant being unafraid of yeoman's work.

“There were two, three of us and it was the same on the administrative end – if you had to pick up some bags and load them onto the truck or plane, you did that,” Gansler says. “And if you needed to tape an ankle, you did that. And if you checked people into the hotel, that certainly wasn't beneath you, either. I don't think he was that rare, but he was certainly humble enough and ambitious enough to do what a lot of people around him were doing, which was to say 'Hey, how can I help? Do you need anything else for me to do?'”

MATCH COVERAGE: US, Jamaica clash in World Cup qualifer

Gulati was politically savvy and patient. And persistent. When Alan Rothenberg was elected as the new president of the USSF, he was advised to promptly clear house from Fricker's administration. Gulati was subsequently axed as the chair of the national-team committee. But he wasn't going to go quietly, and he beseeched Rothenberg to keep him on board.

“Frankly, because I had no alternative person in mind, I acceded to his plea,” Rothenberg tells MLSsoccer.com in an e-mail, “which is the best decision I ever made in my soccer life as he became sooo instrumental in all the successes we have achieved in soccer in the US since then ... and he has become a wonderful and dear friend.”

Gulati was the Deputy Commissioner of Major League Soccer during the league's early days (pictured here in 1996). He says the relationship between MLS and US Soccer is unique in the world of soccer, and the two sides "don't have the sorts of conflicts you see between leagues and federations." (Getty Images )

Gulati, who had been part of the bidding process for the 1994 World Cup, now found himself at the center of the federation's efforts to put on event. The tournament, which set records for ticket sales, helped soccer break back into the American consciousness, and when the time came to build Major League Soccer as part of the cup's long-term legacy, Gulati helped lead the way again.

And as the sport continued to grow, Gulati remained a willing servant, even while continuing his career in economics, having earned his master's degree from Columbia University and joined the World Bank.

“As long as I've been around soccer, he's been there in one form or another, especially with the national team,” says USMNT legend and current ESPN broadcaster Alexi Lalas. “I can remember driving with him [in 1995] from a relegation playoff game in Italy to Milan and then on to Heathrow, and on to Boston and then to Foxboro Stadium, him watching us [Padova] stay up in Serie A and literally the next day being in Foxborough for a national team game [against Nigeria]. It was a crazy 24-hour trip with him.

“He was there to make sure that my passage was secure, and he completed his task.”

* * *

Gulati became a fulltime soccer executive with MLS, serving as the league's deputy commissioner from its inception until 1999, when he joined the New England Revolution front office. Meanwhile, he ascended to U.S. Soccer's executive vice president post a year later and won election to the presidency in 2006, successfully seeking re-election in 2010. The post is not paid; Gulati also works fulltime as an economics professor at Columbia, where his courses are routinely among the university's most popular.

The intimate relationship between U.S. Soccer and MLS has spawned a few conspiracy theories about potential conflicts of interest in federation decision-making, but Gulati makes clear that he has and will continue to recuse himself from USSF processes when necessary. And in his view, it's no accident that a period of tremendous, sustained growth for the sport coincides with the close relationship between the league and the federation.

“The growth of the game goes hand in hand with what the league has done over the last 16 years, and the growth of so much of what's going on in U.S. Soccer,” Gulati says. “The working relationship between the two is extraordinary and my guess is there aren't many in the world that are like that. We don't have the sorts of conflicts you see between leagues and federations – that's a plus.”

To be sure, Gulati has presided over a period of dramatic progress and stabilization for the federation, by any measure imaginable. The shoestring organization depicted earlier by Gansler now boasts a healthy balance sheet with thriving commercial partnerships, ambitious goals and more than $50 million in net assets.

That financial health has enabled the USSF to provide impeccable amenities for its national teams, invest millions in the U.S. Soccer Development Academy; bolster the women's game with the founding and underwriting of a new professional competition, the National Women's Soccer League; and in one of Gulati's biggest gambits, hire the highest-paid, highest-profile coach in USMNT history, Jurgen Klinsmann.

“The federation is in much better shape today than it was years ago,” says MLS Commissioner Don Garber, who also sits on the USSF Board of Directors. “It's in better shape financially, strategically. It's far more organized and professionally run.

Gulati (left) and US national team captain Carlos Bocanegra presented FIFA president Sepp Blatter with the United States' World Cup bid in May 2010. Says Gulati: “I've been part of a successful bid campaign for the World Cup, and an unsuccessful one. I carry lessons from both of those." (Getty Images)

“He's smart, he's fair, he's committed to the game and always can be counted on to do the right thing.”

READ: Gulati talks US youth team success

Gulati is up for re-election next year, and it looks likely that the job of president is his until he no longer wants it.

Beyond the US federation, he has also climbed through the ranks of CONCACAF, a diverse and often murky body where shifting alliances and influence further tested his abilities. His hard-won election to the FIFA Executive Committee new requires him to work on the confederation's behalf in the wake of the corruption scandals that have tarred the reputation of Warner and Chuck Blazer, the enigmatic American who was CONCACAF's longtime ExCo rep before fraud charges brought him crashing to earth earlier this year.

Gulati, then, takes his place among the FIFA elite – which is headed by the powerful yet sometimes gaffe-prone president Sepp Blatter – carrying the burdens of CONCACAF with him. He will come under the microscope in Zurich, where FIFA is headquartered, but, in stark contrast to his predecessors, he comes in with a well-burnished reputation for honesty and morality. He has already served on FIFA's “Independent Governance Committee,” a body created in 2011 in response to widespread accusations of impropriety. (Its slate of recommendations have yet to be fully adopted.)

"Sunil clearly chose to work within the system. That's why he's on the reform committee,” Sports Illustrated journalist Grant Wahl told Grantland.com earlier this year. “He's chosen that instead of publicly shaming FIFA for a lot of the corruption that has happened over the years and has taken down so many of the members of the Executive Committee.”

CONCACAF and FIFA have both come under severe fire in past years due to these scandals. Most pertinently for Gulati and the USSF, questions continue to swirl around the bid processes for the 2018 and 2022 World Cup hosting rights, which were awarded simultaneously in 2010. At that point the Gulati-spearheaded USA 2022 bid was edged out in shocking fashion by Qatar, with the oil-rich Gulf State promising a transformative tournament highlighted by grandiose air-conditioned stadia and a lasting legacy for the entire Middle East.

READ: Gulati forced to deal with disappointment of lost World Cup bid

It was a harsh setback for Gulati and the entire federation, and one that he's quietly devoted to overcoming through the pursuit of the next World Cup hosting opportunity in 2026.

“I've been part of a successful bid campaign for the World Cup, and an unsuccessful one – I carry lessons from both of those,” says Gulati, who hopes to prompt a comprehensive reform of the bidding process in his new ExCo post even as he seeks hosting rights for his confederation – and hopefully his country.

“I think the rules need to be much clearer in two different respects," he continues. "One, what FIFA is actually looking for, what are the main criteria. And secondly, on the whole bid process, the rules need to be clearer on what's allowed, what's not allowed. The other thing we learned is that the role of nation-states has become increasingly more important in these bids, and that's true for the Olympics and the World Cup. The events have gotten to be so big, so important to countries – countries, not just to federations or Olympic committees – that it changes the whole process.

“In the US, being the country that we are, we can't play in the same way. The Olympics or the World Cup in the United States is not going to change the country. That can't possibly be the pitch from a US head of state or a US Olympic Committee or a U.S. Soccer Federation president. In other places in the world, the pitch can be, 'Listen, you can actually change this region of the world or this country by bringing the World Cup here.' And therefore nation-states are involved much more actively in a way that really is almost impossible for a country like the United States, or some others.”

Gulati says he's well aware of the challenges ahead in repairing FIFA's image. "Is it all the way there yet? The answer is no," he says. "Is it all the way where I would like to see it? The answer is no." (Getty Images)

But the questions linger. Is the ExCo a fundamentally dysfunctional body, or simply one that moves in mysterious ways? Did the Qatari World Cup bid succeed by trumping the American (and Australian) competition with a grander vision for the world's biggest sporting event? Or was there something more sinister at play?

And maybe most importantly for US fans who chastised Gulati when the 2022 bid went Qatar’s way: Did the Americans refuse to play a dirty game, and if so, does that reflect naïveté or principle?

Gulati politely declines to discuss unconfirmed allegations about the bid process or other scandals. But he does recognize that FIFA's public reputation has suffered in recent years and hopes to lead reforms from within.

“Listen, it's obviously been a tough few years for FIFA in terms of its reputation,” he says. “I think a lot has happened in the last 24 months to try to deal with some of those issues: the reform process, changes in governance. Is it all the way there yet? The answer is no. Is it all the way where I would like to see it? The answer is no.

“But I think there's progress being made and hopefully that will continue and hopefully I can help influence some of that. … The organization that's responsible for the growth of the game is important, and its reputation is important. FIFA has worked hard to try to deal with some of those previous issues, and needs to continue that effort, to bring change to the organization. It's certainly needed.”

**

For all his achievements to this point, though, successfully finding his way in the rarified air of the ExCo looks like Gulati's biggest challenge yet. He'll need to rely on the fearsome arsenal of skills he's deployed to reach this point, and perhaps even pick up a few new ones on the way.

“We never have all the information that the people on the inside have, and for sure, from afar, you scratch your head and say, 'This is like an empire, the way this works,' with pluses and minuses,” says Gansler. “He's going to have to be as smart and as clever and hard-working as ever if he's going to make an imprint there. For sure, from afar it looks like they play with a different kind of poker chips there. I hope he can help with the broom and tidy things up a little bit.”

Both Gulati's supporters and critics will watch his appointment to the FIFA Executive Committe with aniticipation. Says friend and former US national team coach Bob Gansler: "I wish him well – from afar it looks like they play with a different kind of poker chips there." (Getty Images)

Lalas, who asked Gulati to give his induction speech to the National Soccer Hall of Fame, points to Gulati's personal character as the most hopeful aspect of his ExCo election. Lalas hopes that Gulati can find the delicate balance between pursuing a reform agenda without compromising his mandate to represent CONCACAF's interests, including the aforementioned pursuit of another World Cup.

“I think it's fascinating to see how Sunil in particular will handle this new challenge and what comes out of it,” Lalas says. “Maybe he, more than many, can really be a catalyst for change, although there certainly is the danger of him falling prey...or being a lone voice in the wilderness that gets completely gobbled up and the status quo remains.”

True to his careful, pragmatic nature, Gulati himself avoids grand promises or sweeping statements about the road ahead, preferring to keep a more grounded focus.

“I think the biggest short-term issue is the governance issues,” he says. “So much falls from that. And once those governance issues are addressed, then we can try to do some of the positive things, which is really to build the game continuously – FIFA is financially in very good shape – but you're in a parliamentary situation, you're not setting the agenda for the organization, you're part of a group that does that.”

Gulati has already built a storybook career in the game he loves. But as he now carries the burden of high expectations into the tempestuous waters of the ExCo, he will be urged to please a much broader constituency.

Time will tell if that's possible, but to most observers, he's the right person to have a go.

“He is one of the most ethical people I know," Garber says. “I think that will be very important for him as a member of the FIFA Executive Committee.

"He clearly knows this game inside and out. That is based on years of experience at a variety of different levels, which is unusual for a sports executive. He played the game, he coached the game, he was involved in the federation as an organizer. All those things together, that's a powerful combination of skills.”