THE WORD is MLSsoccer.com's weekly long-form series. This week, writer Charles Boehm examines the role of artificial turf in the future of soccer in North America, and whether or not the surface's critics will one day waver on one of the sport's most controversial topics.

It's a scene right out of a public-relations professional's dream.

Multicultural legions of children, clad in miniature replicas of Manchester City’s recognizable baby-blue jerseys and flanked by their adoring parents and teachers, have flocked to the ceremonial groundbreaking on a sunny spring afternoon in the Adams Morgan neighborhood of Washington, D.C.

Reporters and camera crews from local media outlets are here as well, along with an array of dignitaries and local politicians, including Mayor Vincent Gray.

Marie Reed Elementary School is in the midst of its spring break, but everyone has come to show their gratitude towards the generous strangers who have arranged to transform the dusty, hardscrabble ground under their feet into a cutting-edge, all-weather, synthetic-turf playing field by mid-August, just in time for the fall sports season.

They’re all here because the ownernship group for Manchester City – the reigning English Premier League champions and a club with popularity on the rise in the United States – have agreed to refurbish Marie Reed's heavily used community park at a cost of slightly under $1 million.

Washington, D.C's Marie Reed Elementary School is the fifth school to receive an artificial turf surface via the “City Soccer in the Community” non-profit initiative, but there are plans for 20 more in the future.

By making D.C. the fifth outpost for their “City Soccer in the Community” non-profit initiative – there are plans for 20 more in the future – Man City are providing one of the capital city's most crowded neighborhoods with a precious upgrade in recreational space, especially for youth soccer. The new 60-by-40-yard field's blade-and-infill surface will be professional quality and will realistically replicate a lush grass field while withstanding nearly round-the-clock use by athletes of many ages and activities.

“I'm already getting emails – 'We've got a league of soccer players,' 'We've got an event on this date' – everybody who hears about the field would like to use it, which is totally fine,” says Marie Reed principal Eugene Pinkard, who wears the happy, almost dazed smile of a lottery winner through most of the ceremony. “My goal is that, primarily, it's a great place for the kids, and secondarily it remains a community hub. I think we'll be able to accomplish both.”

Pinkard’s enthusiasm and that of his students is tangible. But it's a far cry from the reaction the installation of the exact same surface would likely elicit from the vast majority of pro soccer players in MLS and around the world, who regularly decry synthetic surfaces.

On this day, however, turf’s staunchest critics are nowhere to be found. On this day, the surface is hailed as the transformative element that will help build a community in one of the most diverse neighborhoods in the United States, and just might hold the key to soccer's next step forward in North America.

---

“It's difficult. You want to try to play good soccer, you need a good surface. And we don't have the resources to have grounds crews fixing fields through all these clubs, so it becomes an easy option.”

-- Claudio Reyna

---

Claudio Reyna still winces when you ask him about the hard artificial surface at Giants Stadium, where he closed out his distinguished playing career with an injury-blighted stint with the New York Red Bulls.

But as U.S. Soccer's youth technical director and the founder and head of the Claudio Reyna Foundation, a non-profit devoted to growing the game in urban communities across the Tri-State area, he also has a front-row seat on turf's slow but inexorable growth into a ubiquity.

“We're going to have places where they need turf laid down so they can play year-round. It's important,” he tells MLSsoccer.com. “In the [U.S. Soccer] Development Academy, something like over 90 percent of the games are played on turf.

“It's normal for kids now. ... They don't think twice, they just play on it. I still have a tough time feeling comfortable with it, to play on it. And it's going to be interesting to see what it does down the road with injuries – are there more joint injuries? It's not natural. But again, it's being used.”

Home to many of the country's top youth club teams, the Development Academy was created six years ago to improve the player development pipeline for the national team.

It is viewed as the long-term wellspring for domestic MLS talent and both the league and the U.S. Soccer Federation have invested millions of dollars in it. And the dramatic extent to which its member clubs have become reliant on artificial turf even hints at a startling idea.

READ: Memorable moments on turf in MLS

What if turf is actually a better surface on which to learn the fundamentals?

Clubs intent on grooming the intelligent, technically gifted players called for in Reyna's 2011 national youth coaching curriculum have come to accept the value of synthetic turf, which is widely used in long-admired European academies.

“I believe it's definitely a positive for development,” outspoken Southern California youth coach Gary Kleiban explains in an email to MLSsoccer.com. “A smooth and quick surface is ideal for technical and tactical training in the formal environment. For instance, if you want to effectively teach possession-centered football, it's best if the players have a field that doesn't get in the way of properly executing technical and tactical activities. Turf is great in this regard.

“A natural field is great too, but only if it is well manicured.”

Kleiban and his brother Brian are the coaches behind the widely respected Barcelona USA program, which helped 13-year-old Californian Ben Lederman become the first American to join Spanish powerhouse FC Barcelona's famed La Masia youth academy two years ago. Brian and his U-13/14 team recently joined Chivas USA's youth academy and will compete in the DA's new U-14 division next season.

The Kleibans are known for inculcating their young players with excellent technique and possession skills, and even in a SoCal region where quality grass fields are more common than in less sunny locales, their players are very comfortable on synthetic pitches.

“The kids want good fields where the ball behaves the way it's intended to behave,” Gary Kleiban says. “The kids love it when their footballing performances are best. That happens on good fields. Turf is definitely considered good.”

Even in Reyna's neck of the woods, limited space, high field traffic and dark, cold winter conditions have made turf the norm, including at the college level. St. John's University in Queens, N.Y., for example, chose a synthetic surface when Belson Soccer Stadium was built atop a parking garage in 2001.

Some youth coaches from New York and other northern climates will even relate that their players are sometimes flummoxed by the adjustment to natural grass when they travel to tournaments in other regions.

Reyna’s accepting of the movement, but he’s a bit reluctant and, he admits, “an old-school guy” on the matter. And he’s not alone.

“I'd rather play on bumpy ground – that's kind of what I grew up playing on, a dirt field with rocks everywhere,” says the Livingston, N.J., native. “It helped me. I think the idea of turf and always getting a flat, perfect ball is not the real game, either.”

---

“If we didn't have turf, they wouldn't be training. The younger kids do train on the turf because that's where they can get the minutes in.”

-- Bob Lenarduzzi

_

Bob Lenarduzzi knows artificial turf – first as a player, then as a coach and now as a club executive.

No one played more games in the old North American Soccer League than Lenarduzzi, who logged an NASL-record 312 appearances as a mainstay for the first incarnation of the Vancouver Whitecaps, the club he now leads as president.

The NASL is remembered almost as much for its predominance of AstroTurf as its collection of dazzling stars from around the world. And for the Whitecaps and their academy – the first Canadian program admitted to the DA – turf is just as much of a necessity now as it was back then.

“I'm not all that sympathetic with the turf-bashing that goes on, because I really believe that it's a surface that has evolved so much since those days,” Lenarduzzi tells MLSsoccer.com. “Artificial turf, when it first came out, it was a thin carpet on pretty much asphalt underneath, so there wasn't a lot of give to it. When I see the condition of the turf now and the competition amongst the different suppliers, it's getting better and better with each version.”

Vancouver Whitecaps striker Darren Mattocks takes a tumble on the turf at BC Place, which was replaced during the stadium's 2011 upgrade. Unlike the surfaces used in Portland, Seattle and New England, Vancouver's is a German-made, FIFA-recommended 2-Star-rated version called Polytan LigaTurf RS+.

- USA Today Sports

The 'Caps play their home games at BC Place, a beautiful yet inherently utilitarian downtown arena owned and managed by PavCo, a provincial authority which stages BC Lions Canadian Football League games and a litany of other events that keep the venue in use more than 200 days a year.

Grass has never been an option. But during BC Place's $150 million renovation from 2008-11, Lenarduzzi and his staff insisted on the most soccer-friendly turf possible, a German-made, FIFA-recommended 2-Star-rated version called Polytan LigaTurf RS+, which can be found at Bayern Munich's training grounds and the home stadia of French Ligue 1 clubs AS Nancy and FC Lorient.

“We laid the turf down when the building was renovated in 2011, and our guys enjoy the fact you're always getting a true bounce on it,” Lenarduzzi says. “In terms of the softness of it, there's a nice cushion. Unlike in the old days, the bounce of the ball is much truer.”

READ: Is turf a problem for the US national team?

This idea isn’t new in Whitecaps camp. Lenarduzzi’s former teammate Peter Beardsley, who starred for the 'Caps before returning to England to become a star with Liverpool and Newcastle United, once praised the synthetic surfaces that even now remain anathema in his home country.

“I think it's great," Beardsley said of the BC Place turf when it opened in 1983. “The ball will stop for you. It does what you want it to do.”

Many of the practical concerns at work in Vancouver are symptomatic of a larger move towards the surface among the wider youth soccer community, especially in the inner-city areas that constitute the sport's final frontier in North America.

“You have millions of people trying to utilize fields at the grassroots level, and some of it is just the practicality of having a safe playing surface that can stand up to the kind of wear and tear that comes from the high level of demand for soccer in this country,” says Ed Foster-Simeon, president and CEO of the U.S. Soccer Foundation, a non-profit which steers millions of dollars in grant funding and programming support towards soccer-based youth development initiatives each year.

Osvaldo Alonso and the Seatlte Sounders have played on the artificial surface at CenturyLink Field since the team's MLS inception in 2009. The stadium will host the US national team and Panama in a CONCACAF World Cup qualifying match this summer, but a temporary grass surface will be installed for the match.

PHOTO: USA Today Sports

A large chunk of the foundation's $60-plus million worth of all-time grant distributions has gone towards the construction of all-weather synthetic fields in response to all that growth, in many cases helping small organizations introduce children to the game without taking on cost- and labor-intensive aspects of turf management like irrigation and mowing.

Though many factors have fed artificial turf's rise, as Foster-Simeon suggests, at its core it's a matter of simple mathematics. The number of participants in the sport (estimated at some 13.5 million, by the US Census Bureau's last count) continues to tick upward, while the quantity of available fields has failed to keep up amid an era of austerity and budget cuts among many local and regional government entities.

Grounds keeping has become something of an artisanal craft, requiring expertise and substantial recurring overhead costs, and even the most carefully maintained grass facilities can be washed out of commission within hours by as little as half an inch of rain.

“If there were only a handful of people playing the game, it wouldn't be a problem – everybody could play on grass,” says Foster-Simeon. “But soccer has exploded in this country, at the youth level in particular, and with the demands on open space, it's just not sustainable to try and maintain grass fields in those communities...Games are rained out because of the weather and thousands of players and families are affected by that.”

Youth soccer's so-called “elite club” level, where players and their parents invest large amounts of time and money in the quest for college scholarships, has also come to rely heavily on turf. Many showcase tournaments advertise their status as “all-turf events,” as teams are more likely to make a long, expensive journey to take part in the event if they know that unpredictable weather conditions won't derail the entire undertaking.

---

"As professional athletes, you can't play a game like soccer on that sort of field. The reaction of players and what it does to your body, as a soccer player, you [need] two or three days off for that. Every game, every team should have grass, without a doubt. You can't ask any athlete to perform at a high level on the FieldTurf."

-- David Beckham

---

David Beckham hadn't even made his MLS debut when he set off the first mini-controversy of his stateside career with those words (right) back in August 2007. Nursing an ankle injury on his first road trip with the LA Galaxy, he elected not to risk making his first league appearance on the artificial turf installed at Toronto FC's BMO Field at the time, and his historic moment instead took place the following Thursday against D.C. United at RFK Stadium.

Beckham’s panning of the surface then in use at four of the league's 13 venues ruffled enough feathers to prompt him to issue an apology, because Beckham was apparently unaware that he had maligned both a company and its lead product by mentioning FieldTurf by name – even as admitted that his own youth academy in London made use of the surface.

But he'd only summed up what most of his colleagues would have considered a plain truth about synthetic grass, widely demonized for being firmer and less forgiving than its natural counterpart. It also absorbs and radiates heat in warm, sunny weather, raising on-field temperatures to blistering levels.

Although former LA Galaxy star David Beckham was often reluctant to play on artificial turf during his MLS career, he scored goals during matches on the surface in both Portland and Montreal.

PHOTO: USA Today Sports

Six years later the locker-room conventional wisdom remains the same, as the anonymous player survey conducted by Sports Illustrated's Grant Wahl revealed on the eve of the current MLS season.

When asked if they would ban artificial surfaces if they had the chance, 15 of the poll's participants said yes, and only three said no. The subsequent question – “Which team has the worst quality field in the league?” – drew only turf venues for responses.

“Most players didn't need any time to think about this one,” wrote Wahl, later noting that “No matter how much some owners would like us to think fake-turf fields are OK, the clear view of the players is simple: They're not.”

READ: Jeff Bradley recalls the MetroStars' early days at Giants Stadium

The number of turf fields in MLS has more or less remained steady even as the league has grown by six clubs since Beckham uttered his withering dismissal of the surface (which he would go on to log plenty of MLS games on, including the 2009 MLS Cup at Seattle's CenturyLink Field).

Under persistent pressure of their own players, as well as the parting remarks of several free agents who elected to sign elsewhere due to the issue, Toronto FC replaced the BMO Field turf with grass in 2010. But it is still found in four markets – New England, Portland, Seattle and Vancouver – as well as the domed stadia where Toronto and Montreal choose to open their seasons due to harsh Canadian winter conditions, meaning that just over a fifth of the league's regular-season games are played on turf.

But at nearly every other level of the game, from youth leagues like those that will blossom at Marie Reed all the way up to adult and lower-division pro competitions – and even the NWSL, the new women's first-division league, where only two of the eight venues feature grass – turf is an everyday reality, home to most, perhaps the vast majority, of the action.

--

"Their turf is good! It’s different from any other turf you play in the league. That’s an amazing one.”

-- Thierry Henry

---

Like many of the players who arrive in MLS from overseas, Thierry Henry is a well-known skeptic of artificial turf who often elects to sit out matches taking place on the surface. But the New York Red Bulls star was full of praise for the pitch at Portland's JELD-WEN Field in the run-up to his team's 2013 season opener against the Timbers.

Henry has made just two appearances on turf in his first three seasons in the league, and both were wild 3-3 affairs in Portland which gave him a chance to experience the features that give the venue perhaps the best synthetic playing surface in the world.

“It was designed and built only for soccer,” Timbers chief operating officer Mike Golub explains to MLSsoccer.com. “We invested in this really unique 'e-layer' subsurface and the fill that we put in really optimizes the playability and feel for soccer.”

An upgrade which added around $1 million to the price tag of the stadium's 2010-11 renovation ahead of the Timbers' entry into MLS, that subsurface makes for a spongier feel that positively affects the ball's bounces and the impact on players' bodies.

Thierry Henry scored a goal and added an assist in his first MLS game played on turf, at Portland's JELD-WEN Field in June 2011. He has never played on the artificial surfaces in Seattle, New England or Vancouver.

- USA Today Sports

“We've had EPL teams play on it, we've had a La Liga play on it, we've had a Mexican team play on it, we've had the [US] women's national team play on it, we have the men's national team playing on it this summer and the feedback has been really considerably strong,” says Golub. “There's artificial turf, and then there's artificial turf, and I think we've got, really, a premier field.”

So why aren't all synthetic fields similarly cushy?

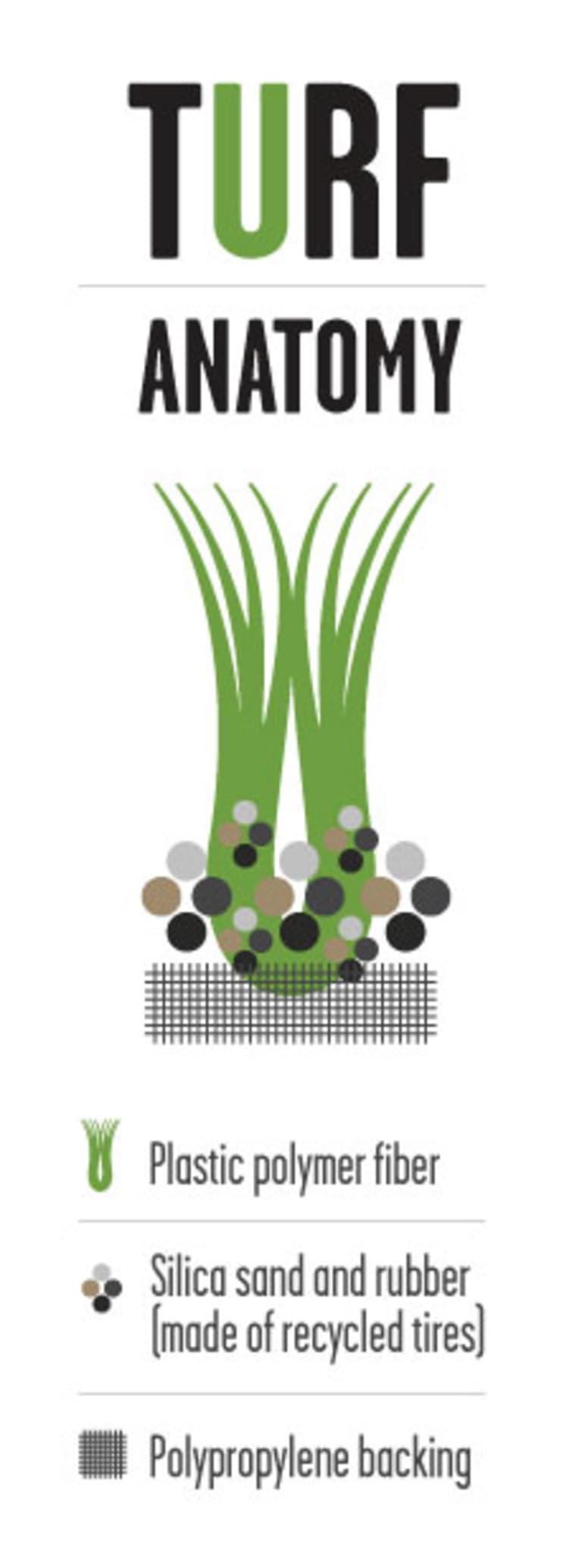

Gridiron football prefers a firmer, faster surface, and in the case of the now-departed Giants Stadium, coaches even directed that their turf be compacted with rollers in order to reduce the softness that soccer players want.

“For a football field the blend is different,” says Golub, who readily acknowledges that as primary tenants at their venue, his club has much less to worry about than do New England, Seattle and Vancouver. “There's clearly challenges to co-existing with NFL teams, because there's compromises that are inherent when you're trying to accommodate both sports.”

READ: Expert says North America behind Europe in cultivation of grass fields

That also extends to the realities of non-sports events and the aesthetics of on-field graphics, which soccer clubs would prefer to avoid.

“The biggest impact on these fields is just their usage, or their over-usage,” notes Ken Puckett, Portland's senior VP of operations. “Also, paint has a lot to do with the life of these artificial fields. If you notice a lot of the venues that share NFL [teams], you have six-foot white sidelines, full-color end zones, huge logos in the middle of the field.

“When you do the conversions back and forth, you get that paint out but you don't get it all out, and over time that paint settles into the fill, down to the nap of the turf. It hardens and you lose part of the softness and the natural feel of the turf. And that's just a natural progression – it's nothing that other venues are doing different.”

Puckett said that his operations staff at JELD-WEN carefully maintains their turf and limits non-soccer activities on it, which include four to five football games per year for nearby Portland State University. The Portland Thorns also opened play on the turf earlier this spring.

The Timbers have not ruled out the possibility of a future switch to grass, though they are amply satisfied with their status quo. Like their Cascadia rivals in Seattle and Vancouver, PTFC academy teams spend the majority of their training and game time on synthetic turf.

The outlook in Seattle is somewhat more complicated. Since their club joined MLS in 2009, Sounders fans have routinely packed CenturyLink Field, where the atmosphere and prime downtown location balance out the necessity of turf brought on by cohabitation with the NFL's Seahawks – even if it has clearly complicated efforts to host big international friendlies and US national team matches.

The US national team will finally return to Seattle to host a World Cup qualifier against Panama in June. But U.S. Soccer insisted on the installation of a temporary grass surface despite CenturyLink's turf having earned a FIFA Recommended 2-Star rating for its playability, the highest certification available. Both BC Place and JELD-WEN Field have earned the same recognition.

“I'd say most fans have accepted that it's turf for now, but that they'd prefer grass,” says Jeremiah Oshan, who covers the Sounders for MLSsoccer.com and SBNation.com. “There are vocal folks on both sides but I think most are just tired of talking about it. The reality is that C-Link won't have grass without massive renovation.”

In New England, the Revolution's joint tenancy with the Patriots has led to a similar mindset. Gillette Stadium once featured grass but was switched to turf in the midst of the 2006 NFL season. In 2010, a higher-grade FieldTurf “DuraSpine Pro” surface was installed for better soccer performance. Revolution officials politely declined to speak to MLSsoccer.com for this story but the club remains active in the pursuit of a new, soccer-specific stadium of their own, for a range of reasons including location, atmosphere and field surface.

---

“If you're going into urban communities, you can't put a full-sized field in. You have to put small fields in and as far as a lot of people getting maximum use out of it, you have to have a turf field or a sport court ..."

-- Cobi Jones

---

Cobi Jones played many games on turf over his lengthy playing career and like Reyna, remains inherently skeptical of it. But as a proponent of American soccer's growing focus on inner-city populations, he recognizes its practical benefits.

But will it even be possible to transition American and Canadian youth players into grass facilities as they mature? The chronic shortage of field space is unlikely to ease any time soon, climatic conditions are an unavoidable factor across large swathes of the continent and many US municipalities are coming to terms with the “new normal” of smaller parks and recreation budgets in these recessionary times.

One East Coast facility manager estimates that a single turf field costs just $10,000 a year to maintain, compared to $25,000 for a quality grass pitch. That sort of ledger-sheet savings is simply irresistible to most bookkeepers.

“There's no turning back from that. We're going to have turf in our lives as we move forward,” says Reyna. “I'm glad, at least at the top, that the MLS has more and more teams that have grass throughout the league.”

Pro teams are able to dedicate substantial resources to the cultivation of lush grass fields by expert ground crews and their specialized equipment (and high water bills). But even that can be a struggle depending on weather and usage patterns. Will it someday begin to look like an untenable luxury?

Consider for a moment how artificial turf's takeover of the youth scene might affect the way the game is learned, played and viewed. If future generations of players regard turf as an everyday reality of their youth and training experiences, will their outlook on its propriety as a game surface evolve, too?

US women's national team icon Abby Wambach recently made headlines for her passionate criticism of the decision to hold most of the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup in Canada on artificial turf. Yet that development only underlines FIFA's growing acceptance of turf.

“If artificial surfaces were not allowed, we wouldn't be hosting the Women's World Cup in 2015, more than likely,” says Lenarduzzi. “So do we want to continue growing the sport both on the men's and the women's side?

“Maybe it can't be as pure as it is everywhere else in the world, but we're certainly going in the right direction, and artificial turf is a part of that.”

---

Back at Marie Reed, at the close of the groundbreaking ceremony, organizers cleverly unveil a dais covered with a parking spot-sized sample of the turf in front of the speakers' podium, which sits in the midst of the downtrodden grass field's biggest bald patch.

The joy on the Marie Reed students' faces is real as they leap and roll on the swatch of green turf for a preview of their school's new amenity. Could one of these children someday help lead the USA to a World Cup championship?

And might that historic moment even transpire on a plastic pitch?

Synthetic turf has come a long way from the days when the old NASL served the world's game to North America on the rock-hard AstroTurf of the 1970s. Now the question may be whether our collective perceptions of the surface can travel a similar distance.