THE WORD is MLSsoccer.com's regular long-form series focusing on the biggest topics and most intriguing personalities in North American soccer. For the complete archives of the series, click here.

In this installment, contributor Tim Froh tracks the unique relationship between Vancouver Whitecaps rookie defender Christian Dean and his brother Josh Huestis, born to the same mother but adopted by separate familes thousands of miles apart. Their bond has helped fuel their success, and keep a family together.

On a chilly night last November in Palo Alto, Calif., Christian Dean was visibly deflated, but not quite defeated.

A standout junior defender for the University of California, Dean was one of the highest-rated prospects in college soccer in 2013 with a sure-fire future in Major League Soccer. But even he couldn’t stop a stunning slide for the Golden Bears, who had just lost for the fourth time in six games and were tumbling from the top of the national rankings at absolutely the wrong time.

Even worse, the 2-1 loss came at Stanford, the school’s bitter rivals from right near where Dean had grown up and first cut his teeth as a youth soccer player.

As Dean and a small group of reporters gathered along the sideline, a towering young college student with a mop of curly hair emerged from the bleachers to meet them. Without a word he calmly passed by the camera crew and guided Dean to a spot on the field out of earshot of the reporters.

Some onlookers undoubtedly recognized him as Josh Huestis, the 6-foot-7 power forward for the Stanford men’s basketball team. By season’s end, almost every basketball fan in the Pac-12 would know his name, after he’d chewed up the conference for a string of double-doubles to lead the Cardinal within reach of the NIT.

Huestis put a consoling arm around Dean's neck and brought their heads together.

“It's super disappointing, but take a lesson from this game,” Huestis said. “Get ready for the tournament, because that's where you'll have your chance. Don't let one loss dictate how you feel about your season or your success.”

With that, the duo returned to the crowd and faced the cameras. How many of those there knew the two star athletes were actually brothers? Some, certainly. Their story had leaked out in the Bay Area by last fall, that somehow a soccer phenom at Cal and a basketball star at Stanford were brothers on a similar path to sports stardom.

But how many knew what the brothers had endured just to be together?

–-

Drafted third overall in the MLS SuperDraft by the Vancouver Whitecaps, Christian Dean could make his debut on Saturday.

(Photo courtesy of Vancouver Whitecaps)

–-

In early 1993, Sutton Lindsey was struggling. She was a single mother who was working full-time in retail in the Houston suburb of Alvin, Texas, and living with her parents, trying to raise her five-year-old son Holden. The long days at work often meant that Holden was asleep when she woke up in the morning, and in bed by the time she returned home.

Lindsey was also six months pregnant at the time, facing a decision on whether to bring a baby into a tenuous situation already fraying at the edges. Unwilling to burden her family with more child-rearing duties and unable to provide her baby with all the resources she thought he deserved, Lindsey decided on an adoption.

As the months passed and Lindsey inched closer to her due date, she and her mother began discussing the details. Who would raise him and where? What kind of a man would he grow up to be? Would she still be able to play a role in his life?

Lindsey and her family had been through this before. Two years earlier, she decided to place her second child, Josh, in the care of the Huestis family in Great Falls, Mont. But faced with the same decision a second time didn’t make it any easier to part with her newborn child.

Dean was born in the Houston suburb of Alvin, Texas, but grew up in East Palo Alto, Calif. His joined his adoptive family just weeks after he was born.

(Photo courtesy of the Dean family)

“I couldn't just adopt them out and not know anything and wonder the rest of my life, 'Are they OK?’” she says. “I knew as a single mother, I couldn't give them what they deserved. I could give them the love, but I knew they needed so much more, and they deserved so much more.”

By that point, Palo Alto social workers Bill Dean and Elizabeth Brown-Dean had been pursuing an adoption for three years with no luck. They’d spent the past eight months pursuing an open adoption with the Independent Adoption Center and gone through training sessions. They put together a photo album and wrote letters to mothers outlining their values, but they still hadn’t received a reply.

But then came a call from the IAC, who put the Deans in touch with Lindsey, and Christian Dean’s future began to take shape. Lindsey felt an instant connection to the couple and embraced the plans they had for her child. She also appreciated that Bill Dean, like Christian, is African-American, and that would help divert unwanted attention from her son and make his transition to a new home in California easier.

“I loved the fact that they were a mixed family,” Lindsey says. “I chose them because I wanted what was best for [Christian].”

Still, one thought unnerved her even into the final month of her pregnancy: “Was he going to love me?”

---

When the Deans arrived at the Lindsey home in Alvin in the spring of 1993, they found themselves caught in a complicated legal tangle. In California, funding for the agencies regulating the interstate placement of children – rules meant to protect children moving between states – had dried up, meaning that the state employees responsible for approving the Deans' paperwork were authorized to pick up the phone but not to return calls.

By the time the Deans arrived, the Texas authorities were still unable to reach their counterparts in California, and the Deans, who had expected to spend a week in Texas at most, were suddenly facing an indefinite stay while the red tape was cleared up.

But what could have been an awkward situation instead transformed into a blessing. After just their first day at the Lindsey home, the Deans returned to their hotel in Galveston with baby Christian, and they were instantly smitten.

Dean at 7 years old in East Palo Alto, Calif. He played a number of sports as a child, but eventually gravitated to soccer in part because of the challenge.

(Photo courtesy of the Dean family)

In the weeks that followed, the Deans got to know Lindsey and her family. During their sixth trip to the home, baby Christian had a crying fit. Whenever he had cried before, Lindsey or her mother would take the child to calm him down.

This time, however, Lindsey’s mother Jane couldn't make him stop. Lindsey herself tried settling him, but he continued to bawl. She passed the baby to his new adoptive mother and the child immediately stopped crying.

“It's done,” Lindsey’s mother said.

After more than three weeks in Texas and with the adoption paperwork finally processed, the Deans made their plans to return to California. As both families gathered outside the home, Lindsey and her mother sang “You Are My Sunshine” for baby Christian. His mother knew she would see her son again, but all of her worries came rushing back to her as she hugged the woman chosen to raise her child.

“The only way I could do it,” Lindsey says, “is if I was a part of their lives as well.”

- - -

Christian Dean was always an athlete. He crawled early. He walked early. He climbed early. To Elizabeth Brown-Dean’s disbelief, the infant Christian even had muscles.

“He was cut,” she says now with a laugh.

Dean played every sport his parents could sign him up for as a kid in East Palo Alto. But after his father threw him into soccer simply because all the other kids were doing it, Dean was hooked on the sport that would define his future.

For a kid who excelled at hand-eye coordination sports, Dean struggled with the foot control that soccer required, and the challenge kept him coming back.

“That drew me to it,” Dean says. “It was something that was difficult for me so I really wanted to get it down. I fell in love with it.”

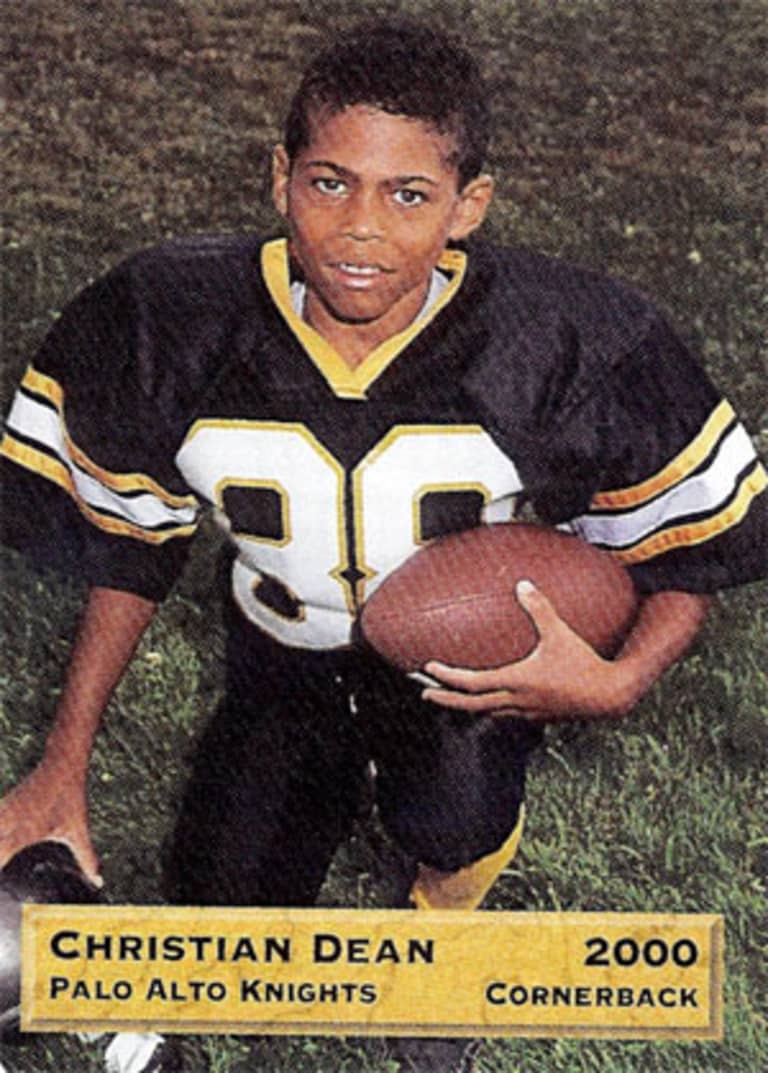

Dean was widely known in the California youth soccer ranks as a teenager and eventually turned down a number of schools to stay at home and attend Cal.

(Photo courtesy of the Dean family)

By the time he was ready for high school, the best academies in the Bay Area were well aware of Dean’s talent and were courting him to join. His parents resisted at first before realizing that the prospect of playing college soccer was too enticing, and he eventually signed with local powerhouse DeAnza Force of Cupertino.

It wasn't long, however, before club soccer’s brutal schedule began to take its toll. Dean felt that all of the weekend games were taking time away from friends and family and he yearned to play football and basketball for his high school. He just wanted to lead a normal teenage life.

By the end of 2009, he was burned out. After spending most of that year directing all his energy towards soccer, he wanted to quit the sport altogether. His adoptive mother knew the problem was deeper, and that Dean quietly longed for the companionship on his older brother, Josh.

The Deans knew that Holden Lindsey was not their adopted son’s only biological brother, and there was another boy, Josh Huestis, who had been adopted and lived in Ulm, a small town outside of Great Falls, Mont. The Huestis family had kept in touch with the Lindseys since 1991, when Josh first left Texas.

Dean and Huestis met for the first time when they were small children in 1995, but neither brother remembers the encounter. Three years later, however, they met again at the Huestis ranch in Ulm. As soon as the Deans arrived, Huestis challenged his younger brother to a race.

“We transitioned right into being brothers,” Dean says, adding with a laugh, “I won by a lot.”

Despite the 1,200-mile distance between them, Dean and Huestis nurtured a competitive friendship throughout their childhood. During their yearly visits, the brothers played basketball, skied, snowboarded, and hunted for gophers around the Huestis ranch. Every competition was a chance for one brother to measure himself against the other.

And as both boys matured, their friendship deepened.

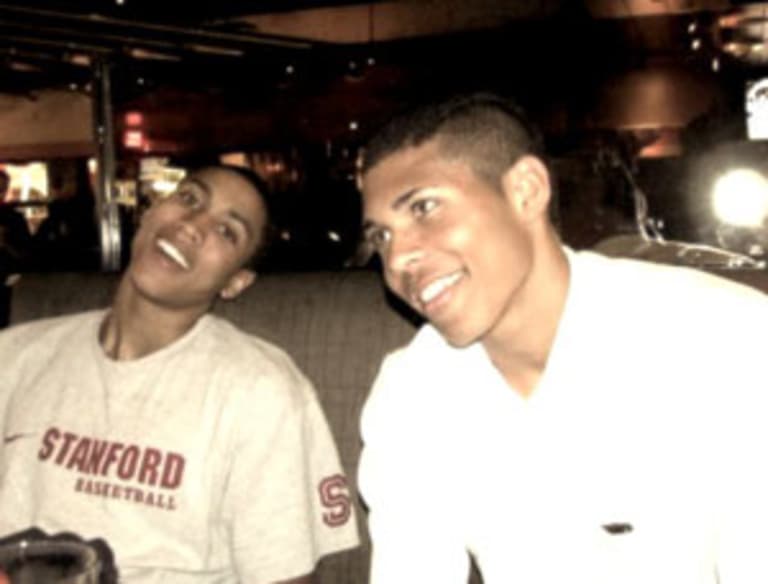

Dean (right) and his brother, Josh Huestis, first met as small children in Montana. They lived together for the first time as teenagers. Says Huestis: "We were inseparable.”

(Photo courtesy of the Dean family)

“We got along very well when we were younger, but I think as we got older we realized that it was really fun to see each other more often,” Dean says.

During a family reunion in Montana in early 2010, the Deans were waiting to board their flight back home to California when the teenaged Christian disappeared at Great Falls International airport. He had gone off to talk privately with his brother on the phone, and when he returned, he dropped a bombshell.

“I'm not going home,” he told his parents.

His parents knew he was struggling with his schoolwork and needed to be back for classes the next day. There was no way he was going to jeopardize his academic and athletic careers to stay in Montana. But neither parent could budge him – “unless I tied him up and carried him,” Bill Dean says now – and they realized it was their son’s last chance to be a full-time brother.

They vowed to explain the situation to Dean’s coaches at DeAnza Force and help him transfer to his brother’s school, C.M. Russell High School, in Great Falls. Then, with Bonnie Huestis's approval, Dean stayed in Montana.

“You go ahead,” Elizabeth Brown-Dean told her son. “We'll figure this out.”

- - -

The Huestis ranch sits just along the Missouri River in the tiny town of Ulm, a 20-minute drive from Great Falls. It is, as Dean describes, “relaxing, peaceful and quiet,” and the perfect place to recover from burnout.

Dean (left) and Huestis as kids in Montana. After they first met as small children, Dean says the pair "transitioned right into being brothers."

(Photo courtesy of the Dean family)

During his six months in Montana, Dean stopped playing soccer and focused instead on building his relationship with Huestis. For the first time in their lives, the brothers were living together under the same roof.

“[The trip] changed everything,” Dean says. “It made me a lot closer to my brother.”

Says Huestis: “We were inseparable.”

The two brothers bonded on their car rides into Great Falls every morning, often times getting up at 6 am and plunging into a blizzard to get to school. As Huestis recalls, the rides were one of the few times during the day when it was just the brothers, alone and finally blessed with the opportunity to catch up.

But as the months passed, the soccer itch returned. While Huestis practiced basketball in the high school gym on his way to being named the Gatorade Player of the Year for Montana, Dean would often find a volleyball or soccer ball to kick around. Huestis knew too well the exhaustion and boredom that can come from the continuous pursuit of a single sport, and he knew Dean was being called back to the sport he adored.

“The time off helped him realize that he loved soccer and that was what he wanted to do,” Huestis says.

In the spring of 2010, Huestis received a scholarship to Stanford University and was set to start school in Palo Alto in the fall. With his brother moving just down the road from his family, Dean knew it was time to return home and start playing soccer again.

Back in California during his senior season, Dean fielded scholarship offers from several top universities. But Cal had something that the other schools didn't – it was just across the bay from his brother.

“He wanted to stay close to home and he knew I was going to be nearby,” Huestis says.

At 6-foot-3 and 200 pounds, Dean was one of the most impressive talents at the MLS Player Combine in January, He's likely to play at left back or possibly center back in MLS.

(Photo courtesy of USA Today Sports)

Dean spent three seasons at Cal and thrived under the tutelage of head coach Kevin Grimes. Grimes saw an athletically gifted player who was talented on the ball, but who still needed to put all the pieces together.

“When you look at his upside potential, it's pretty amazing,” Grimes says. “He has a very unique combination of those elements that you don't see a lot with anybody, American or otherwise.”

Dean helped solidify the Cal defense by his junior season, helping lead the Golden Bears all the way to the quarterfinals of the 2013 College Cup. At 6-foot-3 and 200 pounds, he’s developed into an athletic, imposing left-footed defender geared to play on the outside or possibly at center back as a pro, and he was widely regarded as one of the top prospects in the MLS Player Combine in early January and the SuperDraft in Philadelphia a week later.

Not surprisingly, he was taken third overall by the Vancouver Whitecaps and was a quick fit for the club during the preseason. There’s a starting lineup to crack, certainly, but Dean could make his MLS debut as soon as Saturday, when the Whitecaps host the New York Red Bulls (7:30 pm ET, TSN in Canada/MLS Live in USA).

“He’s a man mountain out there isn’t he?” Whitecaps head coach Carl Robinson said last month. “He really is. He’s big, he’s strong, he’s athletic. I think he’s been phenomenal in preseason. It’s not a pleasant surprise because I knew he could get there, but he’s challenging the center backs for a place in the starting lineup.”

–-

Dean says he has no relationship with his biological father, but he stays in touch with his mother in Texas regularly.

(Photo courtesy of Vancouver Whitecaps)

–-

There is, however, one hole in Dean’s life that likely won’t be filled. He has no contact with his biological father back in Texas and, according to Lindsey, there’s little chance the two will meet.

“He's always known [about Christian] and it's been his choice for no contact,” she says. “I have actually seen him a couple of times ... crossed paths with him. We live in the same area and I haven't really said anything to him, nor him to me.”

Still, he is certainly not without a family. Both of his adoptive parents were with him when he was drafted in January – “an out-of-body experience,” Dean says – and the rest watched from afar. Huestis is ably plugging along at Stanford and nearly averaging a double-double per night on the basketball court, but he’s well aware that his baby brother is making his name too.

“To hear his name called [at the draft] and see all the hard work pay off was just a great feeling,” Huestis says.

And of course he still has his mother, who has been the unifying force in both brothers’ lives. But while Lindsey's adoption decision ultimately led to the boys' success, she deflects the credit. She believes it is the boys themselves, with the help of their adoptive families, who have made their dreams a reality.

“[It's] because they have had the drive,” she says. “And they wanted this. And they've kept doing this. And they've stuck at it.”

And, like any good sons, they’ve paid it all back.

“Through all this,” she says, “they've never stopped loving me.”