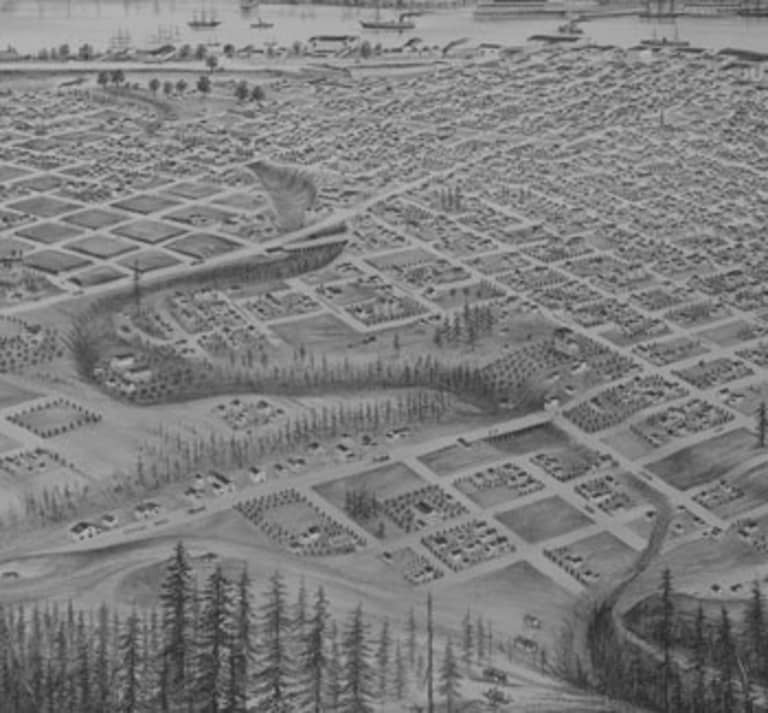

Construction workers began burying Tanner Creek around the turn of the 20th century. It was completed before the 1926 construction of Multnomah Stadium. (Portland's Goose Hollow /Tracy J. Prince)

Tracy J. Prince doesn’t exactly call herself a fan of the Portland Timbers, but she knows when something is going down on the corner of Morrison Street and 18th Avenue.

A longtime resident of the Portland neighborhood of Goose Hollow, Prince says she really only knows the Timbers are playing when she hears the roar of the Timbers Army supporters filing down the street to take their seats at the city’s historic stadium, now officially 88 years old and counting.

“There’s a nine-second delay when the game is on television,” she says, “so I know when I hear the crowd cheer, something good is about to happen.”

Plenty has been written about the history of the stadium, from President William Taft’s emotional address to local children at Multnomah Field in 1909 all the way to the last official game for soccer legend Pelé at Portland Civic Stadium in 1977. They’ve played football, soccer and baseball there, and a dog named Fawn Warrior helped draw more than 35,000 fans to the stadium one day in 1933 during a two-month stretch of races put on by the Multnomah Kennel Club.

And, most fittingly for the Timbers Army’s traditional gameday serenade of “Can’t Help Falling in Love With You,” Elvis Presley nearly caused a riot on the streets when he played to a sold-out crowd there in 1957.

Prince’s connection to the stadium, however, runs far deeper than the events inside the gates. A professor, published author and local historian who consulted on the 2010 renovations before the Timbers' MLS debut in 2011, Prince says she’s one of the few scholars – “possibly the only one,” she admits after a pause – who has devoted the bulk of her studies to the historic area that surrounds Providence Park, the site of the AT&T MLS All-Star Game on Wednesday night.

And what’s left of the creek that has quietly flowed by, while a century of the city’s history was forged 50 feet above.

An artist's illustration of Multnomah Stadium, circa 1926. A different design was chosen, and the stadium has been renovated four times during its lifetime. (Portland Timbers)

Only a limited number of people actually know for sure what Tanner Creek is anymore. Some say they can hear it rush freely under a manhole near the Providence Park light rail station, others think it’s a sewer. Some say the water is only deep enough to cover your bootlaces, but others still walk around Portland today with t-shirts telling the world they kayak’d Tanner Creek, remnants from a DIY approach to cheap thrills in the 1970’s.

Regardless of what it is now, it’s clear what Tanner Creek was before it went underground. Running from the west hills along Highway 26 down into the area that is now Southwest Portland, the creek formed a gulch two blocks wide and roughly 50 feet deep and carved out the natural amphitheater where the stadium sits today.

It also supported more than 20 vegetable gardens tended by the city’s Chinese immigrants and a swath of Hemlock trees. The acidic bark from those trees was essential to operations at the nearby tannery founded by Kentucky politician Daniel Lownsdale, considered one of Portland’s founding fathers.

That tannery – which sat near the site of the current stadium and gave the creek it’s name – also helped Portland become of the main cities of industry on the west coast along with San Francisco, before Seattle and Los Angeles were incorporated.

But there were also risks involved with Tanner Creek and the other streams that crisscrossed Portland’s landscape. Wet winter storms caused the creeks to swell with debris and eventually flood the surrounding areas, making for images like a memorable photo that shows Multnomah Field underwater and the surrounding grandstands in shambles.

An undated photo showing flood damage to Multnomah Field. Civic leaders began burying Tanner Creek around the turn of the 19th century. (Portland Timbers)

Civic leaders took action and eventually completed the burial of Tanner Creek inside a brick-lined culvert at the turn of the 20th century. Environmentally conscious officials diverted some of the water that enters the culvert in 2002 to help convey creek flows and storm water to the Willamette and there have been unsuccessful talks of “day-lighting” the creek, but most of that culvert is the same today as it was more than 100 years ago.

“It looks a like something you’d see out of old London down there,” says Timbers executive Ken Puckett, the man in charge of Portland’s stadium since 2000. “It’s Jack the Ripper kind of stuff.”

The creek has never caused the Timbers any problems – “it’s just one of the quirks that came with the building,” Puckett says – but it wasn’t always easy to find under the stadium grounds. During a massive stadium renovation project in 2000, workers had to repeatedly dig pilot holes in various spots on the property to find the culvert, because city officials didn’t know exactly where it ran.

“Obviously we dug a lot of holes,” Puckett says with a laugh. “We put cameras down there too, and we lost a couple down there. I think they took a left out of the stadium and ended up in the Willamette.”

The creek runs roughly 50 feet underground in most places under Portland, but because the stadium was built in the natural amphitheater already 30 feet below road grade, it’s actually much closer to the surface at Providence Park. Puckett says at one point near the Southeast corner of the stadium – opposite the Timbers Army supporters section – the creek is just seven feet below the foundation of the Providence Sports Care Center, built in 2010.

An artist's illustration of the path of Tanner Creek in the 1870's, eminating from the West Hills to the Willamette River. (Portland's Goose Hollow /Tracy J. Prince)

The creek enters the stadium grounds there and goes under the Providence building before it runs the length of the field underneath the promotional electronic boards beside the pitch. It continues under the Timbers Army section on the north end and then takes a hard right back into the city before eventually emptying into the Willamette near a horse paddock for the Portland Police Mounted Patrol beside the Naito Parkway.

The culvert varies in size – sometimes as small as five feet around, but large enough near the stadium that construction workers are literally in over their heads inside the tube – and the volume of water fluctuates with Portland’s rainfall. The Timbers and the City of Portland’s Department of Sanitation send a remote camera into the culvert every two years to inspect the integrity of the brick wall, but it’s a stretch to find another reason to venture below the surface.

Unless, of course, you’re out for an adventure. Prince says during the 1970s, for example, there was a rush of people who would pry off manhole covers and plunge kayaks into the deep, and then somehow navigate their way out from underneath the stadium and to the river.

Any such activity is obviously illegal, but it doesn’t mean people stopped trying four decades ago. In 2001, reporter Ted Katauskas wrote in Portland’s alt-weekly Willamette Week about a clandestine group of urban adventurers in the mid 1980’s dubbed the Tanner Creek Hiking Club and a man he called Todd, who had a few beers on a sunny Portland day before descending into the sewer in search of the creek.

“They followed it, stooping through a narrow pipe, stepping into a cathedral-like cobblestone chamber,” Katauskas wrote, “walking toward an ominous roar, until they arrived at the Major Sewer Interceptor, a city-sized toilet bowl, where they watched wide-eyed as Tanner Creek disappeared down a swirling vortex nine feet wide and 20 feet deep.”

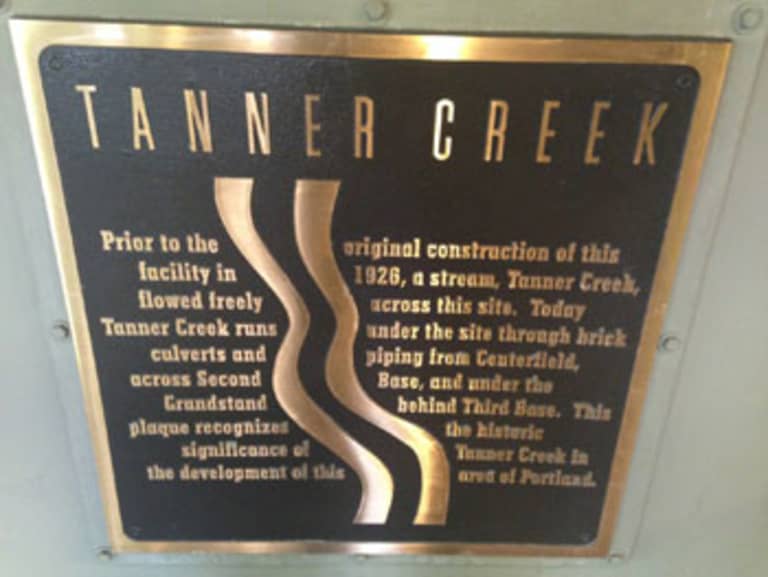

A plaque hangs at Providence Park honoring the history of Tanner Creek. There are also marking outside the stadium on 18th St. showing the path of the creek before it was buried. (Portland Timbers)

Katauskas says now that he can’t remember the real name of Todd or the other adventurers, and he’s never met anyone else who went below. Like Prince, he’s never seen the creek with his own eyes.

A plaque hangs at Providence Park commemorating the peculiar path of Tanner Creek, and there are markings on the sidewalk near 18th Street on the east side of the stadium that show pedestrians what lies beneath.

Prince insists there are spots in Portland where you can still hear the creek too, most notably if you’re willing to crouch down and listen to the manhole cover near the Providence Park MAX light rail station, right outside the stadium.

“If you listen there,” Prince says, “you can hear that creek rushing by, even on a hot summer day.”

And when the heavy rains come back after summer, Prince will walk down to the corner of Jefferson and 16th St., just a few blocks Southeast of the stadium in Goose Hollow, and watch the water begin to pool.

And then, like all water that flows downhill to what's left of Tanner Creek, eventually it disappears down the drain.